A shared journey

The longing of a Mexican American poet speaks for us all. Review: A Face Out Of Clay: Poems, Brent Ameneyro, by Gavin O'Toole

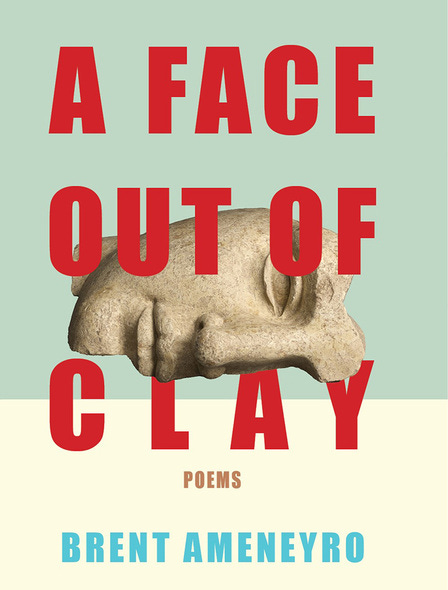

A Face Out Of Clay: Poems, Brent Ameneyro, 2024, Center for Literary Publishing Colorado State University

Candour is the finest virtue and the bitter truth concealed within so much diaspora poetry is that the writer possesses either several identities or none.

This is an endemic condition in a modernity of shifting ground where we all, to an extent, trace the remembered roots of those who have gone before to ancestral sources we reconstruct in half-truths from the fragmented memories of those we love.

It is as true of Mexican Americans as it is of anyone whose family might once have hailed from China, the Levant, Ireland, eastern Europe—perhaps one day even space.

Hybridity is the human condition, which is never rooted and always in transition—and those candid enough to recognise and explore this deserve our attention.

Brent Ameneyro’s poetry is refreshing in its recognition that home is a shifting construction comprised of memory, nostalgia, yearning alongside all the obvious practical requirements of parenting, childhood and the sustenances of living.

That reality is no less profound than our hunger to belong to a mythical past, the deep appetite to know that each of us inherits a millennial connection with a world and time beyond the quotidian that can never be recaptured.

To accept our material, physical presence in the here and now of a given place and time is to embrace the fact that we are simply passengers on a journey whose destination is unknown. It is a worthy thing.

And on that journey, the role of a poet is to reflect upon what might have come before in all its beauty without laying claim to it. The poet is an observer who sketches what he sees or thinks he sees and shows it to his fellow travellers.

Ameneyro does this with cool, clipped style, and it is hardly surprising that one of his influences is Ulyssses by James Joyce, the boldest statement of the writer’s vocation in exploring a journey whose protagonist, at the end, has become a different person to he who started out.

A Face Out Of Clay takes stock of what this means for the poet, whose own family experience like so many others has one foot in a Mexican past—in this case, in that noble city Puebla—and one in an American present.

It is in many ways an exercise in comparison—perhaps in comparative resignation—with the poet seeking to capture the subtle differences and similarities of a people straddling borders.

In “To My Ancestors”, he addresses all of us, for we are all human, yet writes: “… My father/doesn’t like to talk about what’s gone,/that’s why I hide you under my tongue.”

Ameneyro assumes what might be regarded as a typical ambition, to navigate the interplay between Mexican roots and US experience in an effort to reconcile both identities, but one senses that he is also a realist who understand the limits of this task.

“Ulysses in Puebla” is a good example to start with, drawing on Joyce’s classic work, in which a boy from California reflects on the soccer skill of a boy from Argentina as he chooses churros while walking through the market with his family.

There are constant and often clever references to an alien condition which cannot be resolved. In “Roots”, he writes: “They called us los americanos/on the playground/…/The kids at recess knew the word beer, but they didn’t understand root.”

In “The Water Delivery Man”, he writes: “In California, it was the ice cream man./That sweet melody would cut/through suburban cul-de-sacs,/past fathers mowing the lawn/…/In Puebla, it was the water delivery man./That growling truck engine would cut/through cinder block bedroom walls,/past fireworks exploding on the dirt roads.”

There are touching reflections throughout this work that remind us of the proximity so many migrants have to another world that they never lose, and the haze of familial life and love by which their longing is anaesthetised.

In “As the Fog Starts Burning Away”, he writes of a grandmother or elderly aunt: “We laughed in the living room/while Mayté patiently/died in her room. We took turns/talking to her alone because she had/one foot over the border and we thought/maybe God could hear us through her/…”

Imaginative, often poignant, and painted with precision, Ameneyro’s poems add another layer of colour and contrast to the experience of Mexicans in the US by reminding us of the power of remembrance and the sweet and sour legacies of nostalgia.

But what gives these poems their potential to linger is that they extend their arms to address the experiences of us all—inviting us to open our eyes to the beauties of a journey we all share.