Anti-art with attitude

Central American artists are defying their colonial invisibility. Review: Visual Disobedience, Kency Cornejo, by Gavin O'Toole

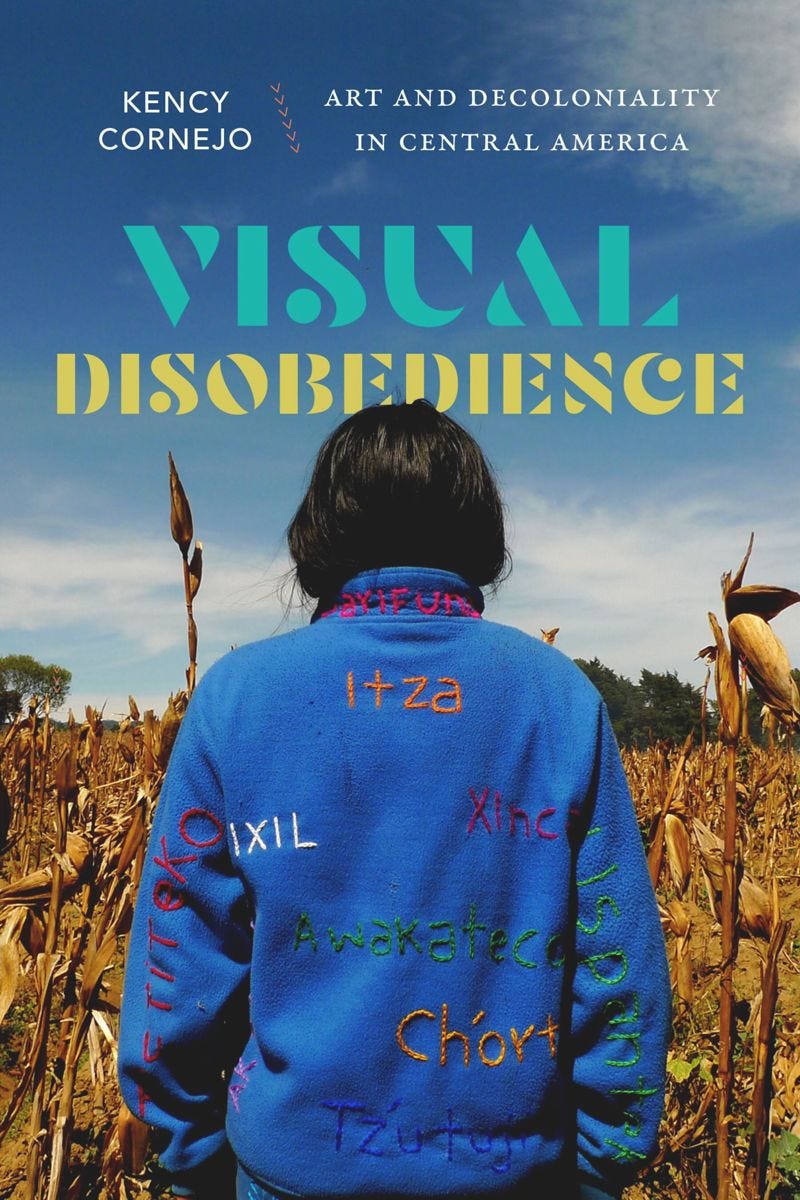

Visual Disobedience: Art and Decoloniality in Central America, Kency Cornejo, 2024, Duke University Press

It is a breathtaking revelation to learn that, to date, no US academic book has offered a history of Central American art, analysed it in relation to the legacies of its own brutal colonialism in the isthmus, or examined the resulting decolonial resistance this has spawned.

Such a powerful observation by Kency Cornejo in itself represents a protest against the sub-region’s invisibility in colonial aesthetics—and the author goes on to offer potent examples of the creative backlash this has given rise to.

It is not a niche observation confined to the rarefied air of university art history departments but one with profound significance for postcolonial studies that extends far beyond the field in real time.

This “erasure” of Central America in the western aesthetic canon represents a reflection—through the lens of culture—of a social reality that continues to be shaped by the impact of imperialism in this part of the world.

Cornejo links erasure, for example, with the migrant “crisis” on the US border as thousands of people escape untenable social conditions ultimately created through Washington’s racist and bellicose foreign policies.

She writes: “The deeper implication of cultural erasure, however, is not limited to inclusion on gallery walls but ripples into sociopolitical spheres in which negation of a people’s culture is historically tied to the negation of a people’s history and humanity.

“For Central Americans, visibility and invisibility extend beyond aesthetics or exclusion from the canons of art and into the denial and erasure of our very existence.”

These types of erasures, she says, are reinforced by an amalgamation of anti-immigrant, anti-refugee, anti-Black, anti-Indigenous, and anti-LGBTQ sentiments in the US that force migrants into obscurity.

Visual Disobedience analyses 40 artists and over 80 artworks to reach a critical understanding of how US imperialism and its legacies fuel the mass exodus of refugees and asylum seekers arriving at the US-Mexico border.

Cornejo’s argument resonates with a loud echo: a Marxist analysis of visual culture would offer wholesale support to both the way in which subalterns are simply denied subjectivity in the creation of colonial knowledge, but also to the way this articulates the dynamics of both oppression and resistance.

The result is a book of great significance that provides a pressing empirical statement not only of how North American and European perspectives still dominate the realm of art—as they do in so many other areas of contemporary reality—but of how this has propelled something of an artistic backlash that is raising art in the region to global prominence.

More importantly, the author does not seek to insert Central American art into western canons from which it has been excluded—but to challenge the colonial logic behind systemic violence in the region by providing a theoretical understanding of creative acts that counter the politics of invisibility used against Central Americans in many ways.

One of the best examples of this that she cites is the performance in 2003 by Guatemalan artist Regina José Galindo, “¿Quién puede borrar las huellas?”, in reaction to the repression of historical memory.

The racist elite had just approved General José Efraín Ríos Montt’s presidential candidacy despite his involvement in genocide during the civil war—from 1981–82 Ríos Montt oversaw the rape, torture, displacement, infanticide and murder of more than 1,771 Ixil Maya people.

Outraged at this amnesia, Galindo walked barefoot between two symbols of power, the Constitutional Court of Guatemala and the National Palace, carrying a basin of human blood, pausing periodically to place her feet inside before leaving a trail of bloody footprints.

Other works analysed make equally powerful artistic statements about the contemporary realities of Central America and the legacies of its imperial brutalisation.

These include the performance of Guatemalan artist Jorge de León, whose gesture at the perpetuity of violence in the region, “El círculo” (2000) saw the artist sew his own lips together in a circular motion to represent the cyclical nature of bloodshed.

Afro-Costa Rican artist Marton Robinson pours white glue over his head as a reference to the whitening agenda of nation-states in Central America.

Indigenous Maya Tz’utujil Benvenuto Chavajay paces back and forth on a busy sidewalk evoking the sounds and memories of the armed conflict and its unresolved injustices—without speaking a word.

Maya Kaqchikel artist Edgar Calel points to the ancestral culture and knowledge Indigenous migrants take with them through photographs in which he wears a second-hand garment sent from the US to Guatemala—traditional Maya clothing bought locally is expensive, and some Maya people, like Calel, cannot afford to own a huipil.

In “No necesitamos más papel” Salvadoran performance artist Alexia Miranda reads the Universal Declaration of Human Rights out loud, then tears each sheet and pinches her body with clips to demonstrate that no peace accord or formal agreement has ended violence in the sub-region.

Honduran artist Jorge Oquelí addresses the failure of the nation by excavating a grave-like hole on university grounds and filling it with muddy water—then plunges in and floats, to evoke the loss of senses that occurs when witnessing overwhelming violence and a criminology process that leaves bodies exposed for visual consumption.

Visual Disobedience is a brilliant and necessary book that makes a valuable contribution to the study of Latin American art and will influence the discipline for a long time to come.

It is instinctively materialist, even though it makes only two references to the Marxist interpretation of culture, notably that of the leading postcolonial intellectual Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, an Indian scholar whose essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” transformed the study of colonialism by exploring political subjectivity in the periphery.

It is the work of Guatemalan artist Walterio Iraheta that perhaps summarises best the cerebral and defiant thread that runs through the artworks considered in Cornejo’s book, with his photographs of a Mayan child and woman by Lake Atitlán—both wearing Superman costumes.

Cornejo writes: “The implication of a Guatemalan Mayan child and woman as an American superhero visually defies the hegemonic representations of Central American mothers and their children in detention centres that dominate media and US imaginaries today.”

At root, the author argues, the creation in Central America of visual narratives that tell local histories as they have been lived is an act of pure defiance.

She writes: “Creation and existence in the face of death and colonial violence will always be an act of insubordination—to the nation-state, to hegemonic narratives, to the violence of erasure, to empire, and to the art world and its institutions.”