Art against extraction

The Latin American imagination is in the global forefront of ecological resistance. Review: Momentum: Art and Ecology in Contemporary Latin America, by Gavin O'Toole

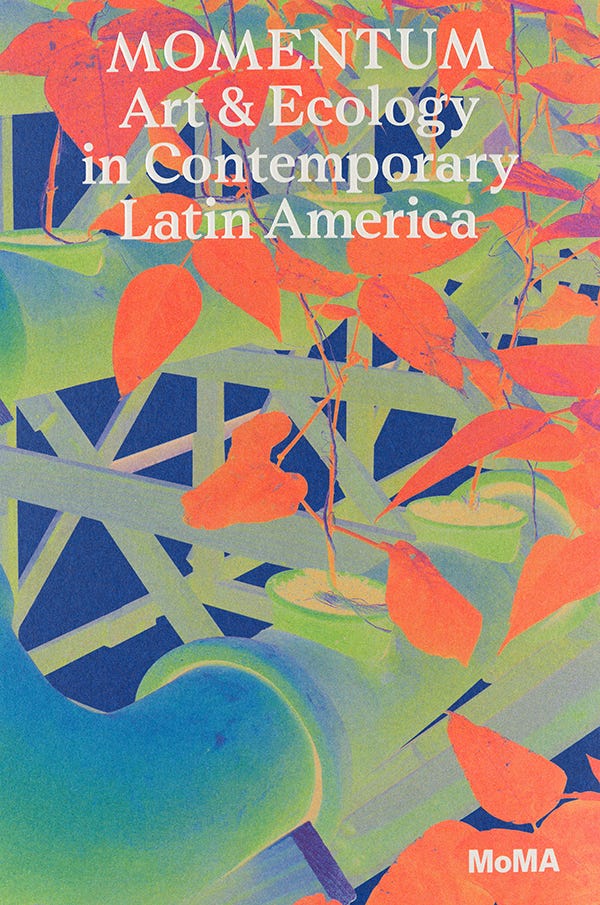

Momentum: Art and Ecology in Contemporary Latin America, edited by Inés Katzenstein, María del Carmen Carrión and Madeline Murphy Turner, 2024, Museum of Modern Art

The rape of Latin America’s natural landscape continues apace, despite volatile commodity prices globally due to geopolitical insecurities.

Putting aside the recurrent political instability in the region caused by that volatility, “neo-extractivism” stubbornly remains the dominant development model, with little sign that this will change any time soon.

Latin America continues to be heavily reliant on commodity exports: about 72% of total exports from its largest countries are linked to commodities, compared to 62% in its nearest competitor, Africa.

It is not hard to understand why: the region is an El Dorado of valuable deposits, holding more than a fifth of the global reserves of five critical metals, vast reserves of fossil fuels, and it already dominates the world in the mining of copper and lithium from salt lakes.

Alongside that, the external appetite for metals like iron and copper, oil and foodstuffs is insatiable—predictably, the US and China are the main export markets for Latin American commodities. In 2023, the US accounted for a staggering 45% of the region’s exports, but China is rapidly catching up.

There has been extensive scholarship on the wide spectrum of negative effects caused by extractivism to vulnerable societies, and how it generates irresistible neocolonial pressures upon weaker countries such as Bolivia and Ecuador.

Exports to the US and China, for example, are poorly diversified overall and commodity heavy, and historically Latin American exporters have consistently failed to diversify into manufactured goods, making them vulnerable to global shocks.

But it is the impact of extractivism on the natural environment in the region that is perhaps the most striking and visual aspect of this rapine development model, compounding the dramatic effects of climate change. Extraction is responsible for air, soil, and water contamination, biodiversity loss, deforestation, and land and soil degradation on a vast scale.

In the path of this apparently unstoppable juggernaut stand many diverse social sectors, and the socio-political conflicts generated by extractivism have also been the focus of considerable scholarship.

Lesser studied protagonists in the ranks of resistance, however, are artists—and, for the first time, Momentum: Art and Ecology in Contemporary Latin America gives us their perspectives.

This book asks what the role of art is in confronting environmental destruction and climate change, and shows that artists in Latin America are at the forefront of a search for answers to this question.

It brings together a wide range of ideas about how the visual arts have been confronting the environmental crisis and imagining alternatives to it in a vibrant array of practices and ideas.

As the first publication produced by the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Research Institute for the Study of Art from Latin America at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, it makes a groundbreaking contribution to debates about the climate catastrophe.

Latin America’s history of extractive colonialism and its unique contributions to global dialogues about ecology make it the perfect focus for such a collection. The region has shaped global debates about the concept of nature as a commodity; played a pioneering role advancing the rights of nature in law; and been a leader in acknowledging Indigenous cosmovisions as models for an ethical relationship to the natural world.

Extractivismo permeates all these dialogues and, as a longstanding historical characteristic of Latin American development, illustrates the continuity between centuries of colonialism and its contemporary legacies reflected in issues such as dispossession and land use.

As contributors to this book note, nor are historically recent, external solutions to the climate crisis necessarily likely to help this region escape its peripheral status in global commodity chains—in some cases they are merely recreating them in a “greener” guise.

Latin American artists are also playing an outsized role, for example, in drawing attention to how the West’s much-vaunted “energy transition” away from fossil fuels to renewables paradoxically entails a new incarnation of extractivism.

The editors of Momentum quote the observation of Thea Riofrancos: “One of the most recent innovations in extractivismo discourse targets the forms of extraction and dispossession that accompany efforts to confront climate change. These are the extractive frontiers of green technology supply chains and the land-use patterns of large-scale solar and wind farms.”

They cite how the transnational Pacto Ecosocial e Intercultural del Sur ecological collective has been denouncing a “new energy colonialism” whose symptoms include new, green pressures generated by the extraction of lithium for making batteries, the land-use problems caused by solar panels, and the extraction of balsa wood for wind-turbine propellers.

Such issues have been debated by artists at conferences throughout the region that have informed this collection, giving context to contributions which consider the role of art in confronting ecological destruction.

In turn, these essays fuel a greater sense that art’s major contribution overall may be to help address the most uncomfortable reality that ultimately underlies debates about nature’s survival—the need to reimagine human civilisation completely.

Artists in Latin America are thinking beyond the impoverished realism of economics or politics, as the Argentine scholar Graciela Speranza suggests, quoting the Zapatista Subcomandante Galeano: “art does not attempt to adjust or fix the machine. Instead, it does something more subversive and unsettling: it demonstrates the possibility of another world.”

Lisa Blackmore does this directly by imagining a postextractivist future, sagely understanding that extractivism contains the key lessons we require for reaching alternative horizons of coexistence and collaboration.

She writes: “By changing conceptions of justice, democracy, and nature, extractivism alters much more than physical landscapes: it modifies the cognitive terrains of how humans relate to non-humans, imposing a utilitarian commodification of nature over other knowledges and practices of relating to ‘earth beings’.”

Grounding her essay in Indigenous cosmovisions, she argues that the complex route out of extractivism not only requires changes to taxation, environmental assessment, a territorial ordering and citizen participation, but also “sociocultural paradigm shifts capable of installing ontoepistemologies that would reclaim and (re)instate ecoethical relations for planetary stewardship”.

She explores art projects that subvert the commodification of nature, such as the collaboration between the Inga indigenous people in Colombia and a team of researchers, designers and filmmakers convened by Swiss artist Ursula Biemann.

The result was the creation of a form of Indigenous “university” that forged transnational connections to collaborate with the Inga on architecture, curriculum design, funding bids, communications strategies, and audiovisual materials.

This marked an inflection in the artist’s work, moving from counterextractivist initiatives such as World of Matter, an art research group launched in 2013 to study global resource entanglements, and Forest Law, a 2014 project with Brazilian architect Paulo Tavares researching the Sarayaku Indigenous people’s successful case against Chevron, towards a “postextractive imagination of knowledges” in which Biemann is just one contributor.

Julieta González also takes Indigenous voices as her point of departure, arguing for an end to the notion that these peoples are “tied to traditional pasts”. We must look in the opposite direction, she argues, towards their own strategies for circumventing the forces of “progress” and “assimilation” by building their own futures.

With her reference point the work of the artist Denilson Baniwa, of the Baniwa people in the Rio Negro basin, she goes beyond artists’ resistance to the rhetoric of desarrollismo in the 1970s by attempting to chart a major shift in the discussion of art and the environment provided by the more recent entrance of Indigenous voices into this conversation.

She does so by considering the Indigenous experience of and interaction with technology and information from outside their traditional realm—and how they have applied this to change the balance of power.

It is a phenomenon with deep historical roots that demonstrated what is possible centuries ago: the Inca Guamán Poma tamed text and image, technologies brought into his world by contact with Europeans in the sixteenth century.

González writes: “Guamán Poma created the matrix from which twentieth-century anthropology could reverse its point of view.”