Culinary colonialism

The corporate takeover of Mexican food is identity theft on a vast scale. Mesquite Pods to Mezcal, eds Verónica Pérez Rodríguez, Shanti Morell-Hart, and Stacie King, by Gavin O'Toole

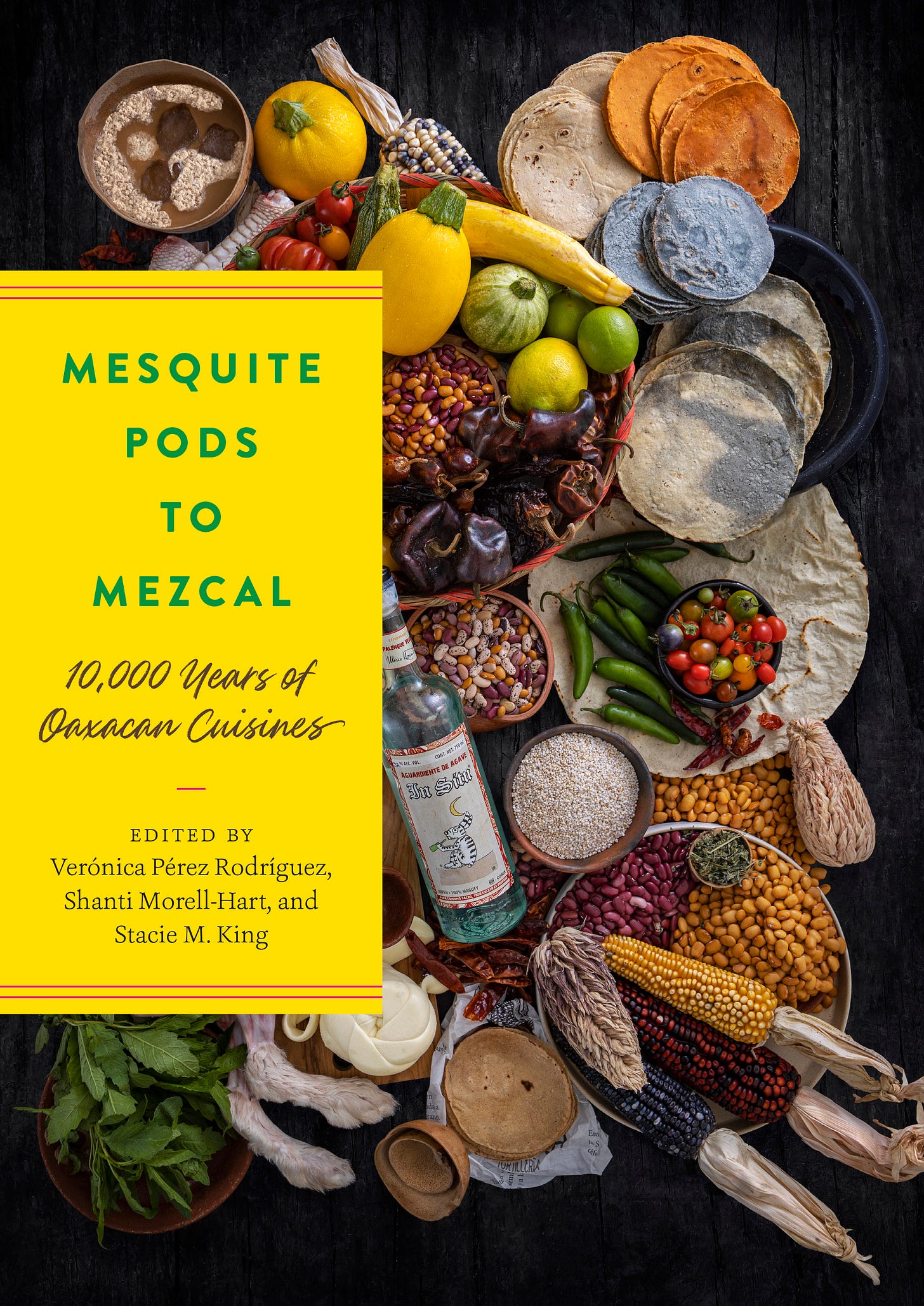

Mesquite Pods to Mezcal: 10,000 Years of Oaxacan Cuisines, edited by Verónica Pérez Rodríguez, Shanti Morell-Hart, and Stacie M. King, 2024, University of Texas Press

When it comes to Indigenous food in what is now Latin America, imperialism in all its forms has generally left a bad taste.

Formal conquest by the Spanish visited dramatic changes on the production and distribution of ingredients used in pre-Columbian foodstuffs.

Ethnocide and rape of the landscape was accompanied by the piratic appropriation of biodiversity and resulted in the invasive and disruptive introduction of new plant and animal species.

Nonetheless, exchange was never a one-way process—while the Spanish introduced livestock such as beef, pork and sheep as well as new dishes, ingredients, and cooking methods to the New World, the colonial centre also incorporated Mesoamerican foodstuffs and methodology.

The resulting “foodways” in Mexico, at least, would make its culinary diversity truly unique, while arguably transforming Iberian and wider European diets with the introduction of tomatoes, chocolate, chiles and maize corn among other ingredients.

Signature dishes and beverages we now associate with Mexican cuisine – from mole poblano to chiles en nogada and even café de olla – were often invented by convent cooks serving Spanish or criollo clerics, and were by definition hybrid.

Unpicking these complex layers of culinary evolution has become the work of specialist scholars, who also highlight the need to recognise regional practices that survived Spanish vandalism and continue to reflect a largely intact Indigenous tradition.

In 2010 UNESCO recognised this “traditional” Mexican Indigenous cuisine as part of the “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”—a welcome and refreshing acknowledgement.

Nonetheless, UNESCO’s inscription is a symbolic act, and one that has often been cooked up to appease demands for the recognition of regional identities. In reality, it is a label that is largely meaningless in the face of cultural imperialism.

The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage has no legal mechanisms to protect intangible heritage against intellectual theft or appropriation, and exists only to promote it, research it and, if necessary, provide technical support to keep it alive.

In short, this UNESCO device is impotent against the modern heir to Spanish imperialism—US monopoly capitalism, whose globally acquisitive appetite poses the main threat to the cultural artefacts the UN seeks to protect.

Indeed, the UNESCO designation in the developing world has often been applied to recognise collective, pre-capitalist practices that are the very essence of the “traditional” precisely at a time when they have become at most risk from Western neocolonialism.

UNESCO’s inscription of Mexico’s culinary heritage, for example, states this pre-capitalist lineage emphatically: “Traditional Mexican cuisine is a comprehensive cultural model comprising farming, ritual practices, age-old skills, culinary techniques and ancestral community customs and manners. It is made possible by collective participation in the entire traditional food chain: from planting and harvesting to cooking and eating.”

What this means is that culinary appropriation has become such a ubiquitous aspect of fast-food capitalism in the “multicultural” societies promoted by neoliberalism that we rarely hold corporate interests extracting global profits from Indigenous heritage to account.

This is a major shortcoming because, as the writer and chef Jenny Dorsey observes, “The way we allow these national and international chains to treat a food culture implicitly shows the respect (or lack thereof) we have for the people represented by these cuisines …”

In short, ignoring the political history of food and accepting at face value a sanitised, neocolonial version of a country’s cuisine that is digestible to a common denominator—fashionably branded “fusion”, when it is usually merely crude falsification—simply reinforces the marginalisation of minorities.

It simultaneously marketises the exotic “other” while expropriating the inherent, millennial knowledge and labour that gave this value in the first place—the intellectual capital created by Indigenous communities over hundreds of generations.

Nowhere is the cultural appropriation of food more apparent than the absorption of Mexican cuisine by the juggernaut of US consumer capitalism—a blatant form of identity theft conducted on a vast social scale.

Not only has the US through the “free” trade agreements it has imposed on Mexico dispossessed millions of the small rural producers whose labours of selection and cultivation created the unique ingredients from which an entire food culture developed—such as unique strains of maize—it has also created perverse new forms of inequality by which quality ingredients once used locally are now reserved for export.

The insatiable demand for Mexican food products such as avocados are also both destroying large swathes of forestry, while creating violent tensions where they did not exist before.

A restaurant chain that has often faced accusations of cultural appropriation is Chipotle—the global fast-food company that has enriched itself on a Mexican-style grilled menu. This corporation is run by an overwhelmingly white suite of executives with absolutely no Mexican heritage.

But there are many others, not least in the UK, who hide behind the mantra of having “fallen in love” with Mexican cuisine and their apparent duty to disseminate knowledge about it in order, in fact, to industrialise it. The degree to which Mexico itself has gained from such a marketing illusion is minimal.

Mesquite Pods to Mezcal, a fascinating insight into the evolution of Oaxacan cuisine since pre-Columbian times, touches upon such themes while reserving its scholarly focus for a more forensic exploration of food history.

It offers examples of both how the continuation of ancestral dietary and agricultural practices sometimes indicate active Indigenous resistance to acculturation, and how capitalism leads to the “gentrification” of traditional dishes and ingredients that, over time, foster new inequalities.

Contributors consider examples of gastronomic revitalisation and “diet decolonisation”, efforts toward food sovereignty that are directly linked to the issue of food justice, primarily from Indigenous perspectives.

By looking at the preparation of the chocolate drink tejate among the Zapotec diaspora in Los Angeles, for example, Daniela Soleri, María del Carmen Castillo Cisneros, Flavio Aragón Cuevas, and David Cleveland show how even a change in ingredients can amount to the persistence of a culinary tradition if the preparation aims to reproduce an “original” dish.

The same contributors also note how maize diversity maintained in Oaxacan communities responds to the culinary requirements and cultural preferences for certain dishes in the face of huge pressures against agrobiodiversity.

They note that the rare maize variety Bolita, used in the preparation of tejate, is accessible to high-end Mexican restaurants in the US that use it for other purposes—forcing immigrant tejateras to use less desired and more readily available mass-market varieties.

“This instance of gentrification demonstrates the phenomenon of appropriation and the uneven nature of access to traditional foods or rare crop varieties, which itself is linked to the proliferation of cheap industrial food and the many obstacles for the maintenance of agrobiodiversity in small farming practices,” the authors write.

While Mesquite Pods to Mezcal is primarily an anthropological history, it draws attention, as Andrea Cuéllar, Verónica Pérez Rodríguez, Shanti Morell-Hart and Stacie King note, to the relevance of studying “foodways” as a window upon cultural, social, economic and political processes.

As a result, it provides worthwhile sustenance on the way to addressing contemporary challenges such as food security, sovereignty, sustainability, and cultural rights.

There is little doubt that for the Indigenous people of Oaxaca, the gentrification of their traditional food—and by implication, of other authentic Mexican foods—provokes a pain in the gut.

Cuéllar, Pérez Rodríguez, Morell-Hart and King write: “Oaxacan food is increasingly appreciated worldwide, in part popularised by streaming food series and online competitions, but such popularity comes at a cost. As cheap and delicious eats such as tlayudas become trendy, their demand rises and so do their prices.

“As with food gentrification elsewhere … those who benefit from the promotion and sale of these foods are rarely the Indigenous people, the cocineras (female cooks), who made them in the first place.”