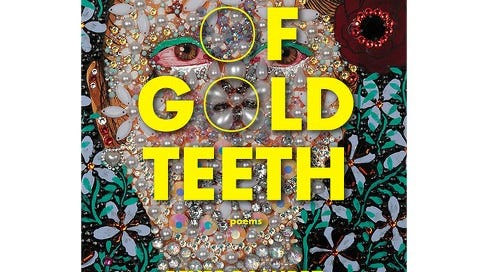

El rey of gold teeth, Reyes Ramirez, 2023, Hub City Press

There is a technical term to describe poetry that combines two languages, macaronic verse, a device as old as the hills from which the voices of poets once resounded.

To intellectual snobs, use of the term macaronic is meant to be derogatory—the word originally derives from the Italian for dumpling, but today is sometimes associated in popular culture with the surname of a football hero commonly known as “Big Mac”.

Yet it was that greatest poet of all, Seamus Heaney, who offered up some flesh to put on the bones of this genre by giving us an insight into the context in which it evolves born of his own experience.

Heaney referred to what he called “hearth language”—the dialect and inventive combinations we first learn within the family and then, as our world expands, our community.

“The point about dialect or hearth language,” wrote Heaney, “is its complete propriety to the speaker and his or her voice and place. What justifies it and gives it original juice and joy is intimacy and inevitability.” Juice and joy. Intimacy and inevitability.

Heaney was well placed to understand this: the poetry of Ireland offers many examples of macaronic verse, unsurprising given that this was a conquered land whose stories were (almost) cut out like tongues and whose dispossessed were swallowed by the English maw. Writers responded with an unconventional, subversive literature that refused to obey the coloniser’s rules and, in time, was recognised for its own genius.

So it is with the work of Reyes Ramirez—also the product of a difficult diaspora—to whom the hearth is literally the origin of all light and whose lavish talents radiate from it with the blazing heat of a chile de árbol.

El rey of gold teeth is packed as full of macaronic verse as a sack of masa and is just as nourishing, able to be shaped into many forms with many fillings, and sprinkled with such sauces as to make one salivate just looking at it.

Ramirez’s debut poetry collection chronicles the origins and destiny of a young, first-generation American with Salvadoran and Mexican heritage negotiating the weird, unsettling lifescape of the contemporary United States.

There is juice and joy throughout these poems, literally. In “Pozole”, for example, he writes:

examine handsome pork & note the vulnerabilities

the ear’s blush, the feet’s foggy tendons,

the ruby pierna’s coat of grasa,

a lightning of white cartilage.

…

taste this labor. taste what’s been tasted before you,

what has provided clarity beyond hunger,

what has been prepared to the singing

of those who cannot hear your music,

by those now in unwakeable sleep

And there is intimacy and inevitability. In “IV. Hijo, please” he writes:

Entiende que all times es hard. Los malos siempre estaran in charge, y los buenos sobreviven. What can you do? If you love god, you surrender what you love most to him. Y si no confias en la justicia, no existe. If justicia is not true, que estamos haciendo.

The many voices in this collection wear their marginalised condition like a mask, and exist in states of intimacy and conflict almost simultaneously. This is the life of the migrants’ son, a dazzling, enriching, confusing, bittersweet concatenation of remembered sounds and sights.

But throughout, there is that resonance which speaks to Heaney’s observation. We recognise in Reyes’ use of language the echo of ethnic inheritance still, so easily lost across generations but captured by the poet like a moth under a lamp.

His poetry quivers with the living history of a people who are there but not quite, and the signs he has spotted of their dying moments or their triumphant survival against the odds.

Such recognition can be a comfort for a writer but can also be a torture, because it is a reminder at all times of the fragility of the cultural memory that they are seeking to record, the delicate archive of sentiment that defines us all.