Library of forgotten saints

Mexican American poet Jose Hernandez Diaz explores the mystery and magic of existing within two cultures. Review: Bad Mexican, Bad American, by Gavin O'Toole

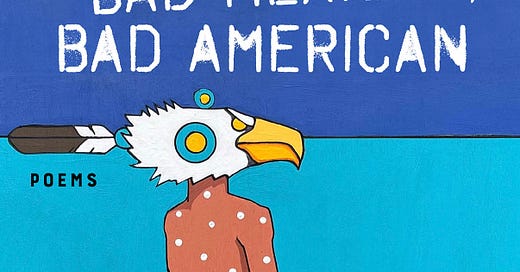

Bad Mexican, Bad American, Poems, Jose Hernandez Diaz, 2024, Acre Books

Sure, we can try to improve, but we have nothing to prove, Jose Hernandez Diaz feels like telling his father.

But he doesn’t—maybe out of respect, maybe because his father will not listen, maybe because the old man is just exhausted from working all day. So he turns up the volume on the Laker game.

It is a conversation never had between an immigrant and his son that has probably been repeated a million times—an unspoken dialogue that is the beating heart of this moving introduction to the inner life of a Mexican American, the poet’s debut collection.

It is shared with a clarity and simplicity—minimalism is the description used by champions of this Californian poet—that combine to make the thoughts of Hernandez Diaz refreshingly lucid, and hence to make the reader wish he were there watching, listening, and learning.

The outcome is an imprint, a memory shared, a real understanding of the condition of a Mexican ostensibly trapped inside an American—or perhaps an American trapped inside a Mexican—and hence of a next-generation immigrant displaced in a dimension of being that is not yet quite there, perhaps to be realised but who knows, and does it really matter?

He writes: “I like football, ketchup on my scrambled eggs;/My biggest sin, perhaps, is I speak English to my parents./I’m a bad Mexican. Yet I like carne asada over BBQ,/Latina women who speak Spanish in my ear./I root for México in soccer. I’m a bad American too.”

Given this, Hernandez Diaz is right to say “we have nothing to prove”. His poetry does not possess a second-generation insecurity but a confidence seated firmly upon the firmament by which Mexican culture in the US is grounded—certainly more confident in its kinship than the fragmented American way of life that tries to suffocate it, and possibly even more solid than the shifting tectonic plates of Mexico itself in terms of both geology and society.

This is captured well in “The Conformist”, in which a man in a Neil Young & Crazy Horse shirt passes through an empty day that he fills with inane activities—coffee, gym, American football—“He was conforming very well to society; he was living the dream.”

After all, the poet writes, “true education lies in your roots”, an instinct that seems to drive so much Mexican American creativity. That is probably because of the relative proximity of familial roots afforded by a shared frontier in comparison to other Latino communities. Mexicans can literally reach out and touch the ancient yet living spirit of their homeland—Americans cannot. As Hernandez Diaz says, “I was born in a small apartment with giant roots that cracked the pavement.”

The poet explores those roots through sweet longing in crafted yet unpretentious language that does not seek to dazzle yet certainly amazes. English and Spanish dance effortlessly as equal partners in a display of natural familiarity.

At the core of this performance are the personalities that define a community absent of privilege: his parents Maria and Esteban to whom the collection is dedicated, family, friends, their families. This is the landscape of humble circumstances but noble perspectives. Elites find it all but impossible to write like this. Hernandez Diaz recognises the real wealth possessed by anyone with a close family.

“I don’t talk/about my personal life much. Why/complain? I had a loving family who/took care of me. A roof over my head./Beans and tortillas on the stove.”

At its core are his parents, and this loyal son is overwhelmed with touching gratitude for the sacrifices of these heroic people. This is evoked with beautiful rage in “My father never ate until everyone had eaten” in which Hernandez Diaz is overcome with appreciation, for “now I know, I ate because/of my father’s sacrifice, and there is nothing: no painting, or poem,/as beautiful as a father’s ineffable love.”

“My mother’s ‘broken’ English” is a short masterpiece of affectionate observation, in which the poet captures how her use of language “Will comfort you like a sarape./Is not afraid of the dark./Is commanding yet vulnerable./… Has taught me how to read poetry./Has become masterful over the years./Sounds magical in prayer.”

But there is a substrate of injustice running through this work, just as there is in the daily travails of any underclass having to deal with the unnatural hierarchy imposed by inherited privilege.

Hernandez Diaz writes: “Most Black, Brown, poor kids in the hoods, barrios, and trailer parks/Are starting from behind their privileged neighbors in the suburbs./Survival of the fittest? Protestant work ethic is not the same/As centuries of privilege.”

He considers the possibility of not being a capitalist in a capitalist world, a transcendental realisation captured by a man staring out across the sea. He works a Wolverine mask along Hollywood Boulevard to make a few dollars from tourist snapshots.

Hernandez Diaz has mastered the short paragraph of poetic prose that captures a moment in time and space brimming with ideas, feelings and colours. This poet is on a poignant journey and is constantly bemused by the unexpected images he encounters along the way.

This is the sensibility of the displaced, or the almost displaced, who look at a world around them which appears newly formed, curious, surprising: Quetzalcoatl at Panda Express ordering the “impossible orange chicken” bowl.

The dreams and recollections the poet shares are the entangled paraphernalia gathered by all young Chicano men, poets, romantics, sons—of being a French Existentialist novelist; meeting Octavio Paz on Jupiter; going on a date with Frida Kahlo and kissing beneath a Siqueiros mural; of many exploits in a Pink Floyd shirt.

His publicists suggest this is the influence of surrealism, which offers a humorous and sometimes bizarre collage of moments that the reader will search for hidden meaning. It may, or may not, be there. As the man in the Chicano Batman shirt said, “Life is kind of crazy”.

Yet there is also often a common thread to this melange and it is the pull, like the taut strings on a bajo sexto, of the Mexican heartland—the man in a Chicano Batman shirt also got a rooster tattoo … then dreamt of his family’s rancho back in México.

This is when Hernandez Diaz is at his best: my favourite poem in this collection is “Doña Ofelia”, a delightful memory of accompanying his cousin Jesús to the airport to pick up his grandmother, whose story Jesús, “Jesse”, then asks the poet to write.

“I say that all it takes is one moment, like the story/about the beans and the bolillo and the neighborhood kids,/to say something special about someone. As for Doña Ofelia,/I tell him, she is part of the old ways of México./“We are lucky to have her,” I say.”