Memoirs of genocide

An American present during Guatemala’s civil war offers timely recollections. Review: Walking With Evaristo, Christian Nill, by Gavin O'Toole

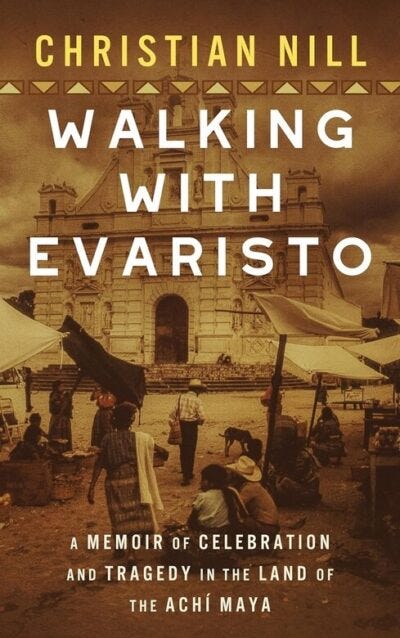

Walking With Evaristo: A Memoir of Celebration and Tragedy in the Land of the Achí Maya, Christian Nill, 2024, Peace Corps Writers

The irony of being a US “Peace Corps” volunteer in Guatemala during the early 1980s—when Washington’s “war corps” was fomenting genocide in the country—is not lost on Christian Nill.

The author of this memoir spent over three years in Guatemala, witnessing at first hand an unfolding slaughter of indigenous campesinos that lacks a modern comparison anywhere in the hemisphere, and his book is suffused with sadness and guilt.

Sometimes referred to as the Maya genocide or Silent Holocaust, the Guatemalan genocide was the wholesale extermination of indigenous civilians by successive US-backed military governments during the Central American country’s civil war, which ended formally in 1996.

Massacres of entire villages, disappearances, torture and summary executions of civilians at the hands of security forces—which crudely conflated campesinos with leftwing guerrillas—was an explicit policy pursued by military regimes in the full knowledge of their US masters.

Nill was in Guatemala as this scorched earth policy was reaching its peak: in the period of the Silent Holocaust itself from 1981–83, of the 162,000 victims of military bloodlust 134,600 were Mayans, 83%. It was mass murder on an epic scale.

The US was directly implicated in this crime against humanity—it funded, equipped and trained the Guatemalan forces who carried out the slaughter on the ground, and almost certainly provided logistical support and intelligence.

Declassified US government documents have shown that from the 1960s, the CIA trained the Guatemalan military in covert techniques of repression, including kidnapping, torture, disappearances and executions of anyone suspected of leftwing activity or even sympathies.

Washington maintained Guatemala’s generals in power, gave them political legitimacy, conspired against their opponents, turned a blind eye to their excesses, and shared their strategic objectives—to eradicate progressive influences in the sub-region. This was a US proxy war.

And to this day Guatemala’s indigenous hinterland remains traumatised while its ladino elite retains control over the levers of power and continues to benefit richly from command of the economy and national resources.

While the dictator General Efraín Ríos Montt and his former intelligence chief were eventually convicted for genocide and crimes against humanity, Ríos Montt’s conviction was later overturned on a technicality. Moreover many, many more perpetrators of the most heinous crimes have never faced justice and continue to live freely.

Ríos Montt was himself emblematic of US strategic interventions in Central America at this critical period in the Cold War—receiving specialised training at the US-run officer training institute that became known as the School of the Americas, and later at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. America taught him how to massacre his own people.

Nill’s memoir is a candid account of his forestry work in Guatemala in this period as a Peace Corps volunteer in Rabinal, a municipio of 20,000 people situated in the department of Baja Verapaz in the middle of the country.

His assignment was to assist the national reforestation effort, which at the local level meant helping to develop and manage a tree nursery and teaching campesinos about planting techniques and soil conservation.

It was a noble aim that undoubtedly did good work—but the author is candid and confessional about the guilt he continues to feel about his presence during Guatemala’s long nightmare, and his own powerlessness to act.

Rabinal was stained with blood—the author lost personal friends and colleagues to army atrocities and was present at the time of, if kept away from, one of the worst massacres of defenceless indigenous peasants in the town plaza.

With chilling recollection, Nill reflects on what was transpiring a few hundred yards from where he was staying as nearly 200 Maya were gunned down without pretext by bloodthirsty troops out of control.

He tells us of the forced draft of campesinos by the military and how, for those who refused to join vigilante patrols created by the army, the punishment was death.

Such was the banality of evil in this period, that the title name of his story, Evaristo, refers to a friend Nill made who was disappeared and murdered on the same day that he had run in and won a village marathon.

This eloquent and moving account contributes in its own way to the body of testimonio literature from the period, while also providing the unique perspective on what transpired in Guatemala of an American citizen.

As a witness to the results of mass murder inspired by his own country, Nill offers us the insights of an American upon whom the heavy toll of its imperial vocation in Central America is slowly dawning.

It’s timely to be reflecting on this, as the US government empowers Israel to commit genocide against the Palestinians—undoubtedly drawing upon lessons it learned during this period. The Jewish state not only sold weapons to the Guatemalan regime but also provided military advice that contributed to the war crimes it committed against its indigenous population.

But Nill’s story also provides a unique interface between the aims and outcomes of US “hard” and “soft” power—reinforcing questions that must be asked about the ways by which governments that with one hand fund development (and human rights) initiatives, while with the other undermine the potential these actually have to do good work.

The Peace Corps—an agency of the US government—has never been without its critics in both the US itself and in Latin America, primarily on the left, who dismiss it as a vector of capitalist imperialism, neocolonialism and racism (as the embodiment of the “white saviour”).

Observers and former volunteers have argued that Peace Corps programmes have served to legitimise dictators and anti-communism, and their presence in a country has often been in conjunction with US military interests.

Yet it is clear from Nill’s account that he was committed to his work and, from religious or philosophical commitment, was seeking to do the right thing by helping Guatemalan Maya peasants in a concrete way. There are undoubtedly many, many volunteers just like him.

It is also clear that he discovered truths in Guatemala and particularly among the Maya—whom he came to love—about himself and his society which changed him for the better.

In that respect alone, if we interpret Walking With Evaristo solely as one man’s journey towards enlightenment, this book makes a worthwhile contribution to our understanding of this dark period in history, and we should be grateful to Nill for having had the courage to write it.