Paradise found

An Australian exile’s adventures in Colombia are a perfect cure for the malady of stereotypes. Review: Better Than Cocaine, Barry Max Wills, by Gavin O'Toole

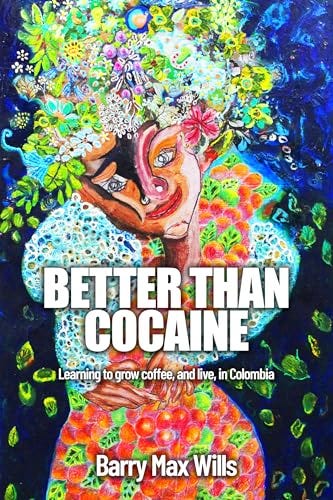

Better Than Cocaine: Learning to grow coffee, and live, in Colombia, Barry Max Wills, 2023, Fuller Vigil

There is a special place in Australian culture for expatriates and it reflects a curious feature of exile, which provides those who live in another country a power of observation that standing still can never equip us with.

It is as if exile itself were a lens that, used with curiosity and imagination, magnifies the human condition to the point where it can be seen with more clarity and understood more profoundly.

This may help to explain the compulsion of Australians to travel—their celebrated wanderlust—but also the fascination writers appear to possess for whatever they encounter, what Robert Hughes would probably have called “the shock of the new”.

And Australia is one of the great exporters of expatriate writing talent—I myself have worked with Aussies, whose humour, drive and refusal to defer to tiresome British class conventions is not only a revelation but gives them a certain critical insight.

However, the destination of what might be called Australian “diaspora” writers is more often than not the English-speaking world—in the UK such visitors as Hughes, Clive James, Germaine Greer, in the US Peter Carey, Sumner Locke Elliott, Shirley Hazzard etc …

Less well known are those Australians who have thrown convention to the wind to step outside their comfort zone into the truly unfamiliar.

Whether it was Barry Max Wills’ original intention to do so, or happenstance, stepping “outside the comfort zone” is a fitting metaphor for his book, Better Than Cocaine, and also for the philosophy that ultimately guided him to writing it.

Part memoir, part travel book, this is a story about an intrepid Australian with a characteristic determination to escape his comfort zone and experience the world he discovers—and also fashions—in Colombia.

It is an absorbing read for that Latin American dimension in itself, but also for being a perfect introduction to a country that, in the author’s experience, has undergone rapid change in the years that he has spent there.

But above all it is a love story—one about the leap of faith taken by one person prepared to venture into the unknown out of love for another; but also about the equally deep love of an inquisitive man for the new land in which he then finds himself.

Describing himself as “half Australian, half British and half Colombian”, Wills spent 40 years as a freelance writer in the corporate sector—which explain his evident skill at storytelling—but for the past 20 years he has also been a coffee farmer in the municipality of Anserma, a small city in Caldas department at the heart of Colombia’s coffee-growing axis.

Those more familiar with him will know him from his regular despatches—his “Letters from Colombia”, initially penned to demonstrate to his family that he was safe in a country whose reputation precedes it.

The book tells the story of how in 2001 Wills and his artistic partner Adriano Zamudio bought an abandoned coffee farm in the Colombian Andes called Rancho Grande at a time when coffee was almost worthless and guerrillas were kidnapping “anyone rich enough to own a refrigerator”.

The narrative is built upon the evolution of their coffee business—successfully resurrected and expanded to nine farms and three principal residences to the point where it is a large, viable going concern tapping into a growing awareness of and market for certified, sustainable produce.

In bringing Rancho Grande back to life, Wills and Zamudio display an intoxicating settler spirit—but of the best kind, to revive the land and unlock its fertile potential in a collaborative way that also enthuses those who have hitherto seen only limitations. It is the best kind of adventure, an exciting mission to build something positive from scratch.

They do so with the help of family, neighbours and friends, whose multicoloured stories of passion, loyalty and betrayal are what has made Colombia an object of such fascination ever since One Hundred Years of Solitude¸ one of the world’s greatest novels.

Wills possesses an emotional intelligence and expatriate eye which equip him with a sagacious perception about the quirks and foibles of those he encounters. As a writer, he understands colour and contrast—Colombia is so vibrant precisely because there has been so much darkness in its story.

Each chapter recounts a step forward in the couple’s progress towards commercial viability, self-sufficiency—their first full harvest in 2007 gave these novice cafeteros a return on their labours for the first time—and achieving the lifestyle they aspire to.

They make frequent moves between residences until they settle upon a property they name Mykanos which they transform into a comfortable home. As a gay couple without children, at the heart of their lives are their pets—in particular their beloved cats.

But each chapter, in keeping with Wills’ original “Letters”, also tends to discuss a theme that will enlighten readers about Colombia—from the omnipresent concerns about kidnapping, guerrillas and bandidos, to the ever-present issue of marital fidelity, colour schemes, history, Christmas fiestas dressed as Santa, and the Miss Colombia pageant. Although the couple have travelled the world extensively, Anserma and its surroundings are the principal focus.

Wills traces the interesting evolution of attitudes towards homosexuality in a rural, Catholic, society, not least those of his partner’s traditional father and how, eventually, they formalised their unión marital in 2010—a status for same-sex couples introduced in Colombia in 2007, just two years after the UK but a full 10 years before Australia.

On this journey, Wills and Zamudio display a commercial nous—but above all an ability to imagine the possible—that is reflected in a growing expertise on the market for coffee and the policymaking environment.

It is not all plain sailing—there are ups and downs, determined largely by global commodity prices, but it is clear that the author and his partner become something of authorities on this business during the course of the story, to the point where the couple are confident enough to collaborate with fellow farmers in the paro cafetero, the coffee-growers’ strike, in February 2013 to demand more government support for the sector.

But Better Than Cocaine is also the story of modern Colombia, which Wills has chronicled during an historic transition from a generation of civil conflict to the more hopeful, if messy, peace that prevails today. This has allowed its society to begin flourishing in ways that Wills has captured with the skill of an ethnographer.

One of his most laudable missions has been to puncture the negative stereotypes that persist in painting false images of a country racked by violent conflict, drug-trafficking and corruption.

Those things clearly remain shadows in the background of this story—insecurity is a prevailing theme—but as the author writes, today Colombia is attracting international attention for the right reasons: its beauty, passion and hospitality.

The negative baggage accumulated by outsiders very much reflects the exception rather than the norm, he says, quoting a British expat who told him: “Everything bad that you hear about Colombia is true. But so is everything good that you never hear.”

Indeed, the title of the book is a play on this, with Wills noting that “Colombia was much more famous for cocaine, guerrilla wars, kidnapping, random violence, murder and mayhem than for holiday homes, health and happy endings.”

For this stereotype-bashing reason alone, I would recommend that visitors to Colombia read this on the plane or pick it up at El Dorado International Airport upon their arrival—one hopes it is already on sale there. Better Than Cocaine is probably the best real introduction to the country and its people, written with both humility and humour, you are likely to find.

The author paints a sensitive and sympathetic portrait of a community that has overcome the constraints of a troubled history with a zeal for life that is inspiring—this is Latin America at its best, captured perfectly in the title of a TV hit from 2006, Sin Tetas No Hay Paraiso (“No Boobs, No Paradise”).

As Wills points out with characteristic attention to detail, the canny boast of Colombia’s tourism board today is: “The Only Risk is Wanting to Stay”.

Wonderful, thank you!