The helpful dead

Two books about death. Reviews: The Intimacy of Images, Myriam Lamrani; and Moved by the Dead, Michael Amoruso, by Gavin O’Toole

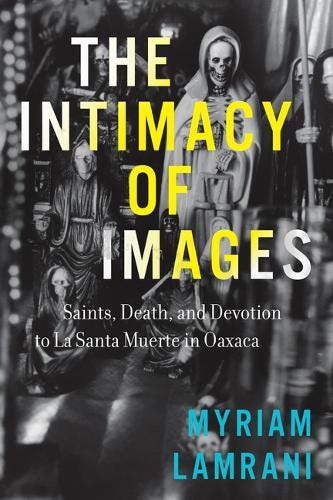

The Intimacy of Images: Saints, Death, and Devotion to La Santa Muerte in Oaxaca, Myriam Lamrani, 2025, University of Texas Press

Given the extent to which violence has permeated the way of life in swathes of Mexico, it is hardly surprising that people pray to death itself. Literally.

Saint Death, or La Santa Muerte, is a well-known ghoulish character in the iconography of popular worship—often depicted as a skull in a wedding dress carrying a scythe.

It has been estimated that the cult has up to 12 million followers in Mexico and within the Mexican diaspora in the US and Canada.

It has also been adopted by drug traffickers who ask the saint to intercede so they can avoid arrest and make money.

Contemporary portrayals of La Santa Muerte, who is also known under a series of other names, depict her as a young bride who died of sorrow when her groom abandoned her at the altar.

Images often show her as a youthful woman or a winged angel with one side of her face missing flesh. Today she is commonly characterised as a female grim reaper brandishing a scythe and occasionally holding the world in her other hand.

The origins of this character reside somewhere in the dark recesses of colonial Catholicism or perhaps even Aztec death cults, and author Myriam Lamrani explores the striking imagery associated with this fascinating subject.

Lamrani traces the historiography of La Santa Muerte and how she has periodically appeared and disappeared in anthropological accounts, in recent decades obtaining an association with the state and city of Oaxaca.

In 2001, Enriqueta Romero established an altar to her in Oaxaca and the cult of La Santa Muerte began to gain increased visibility in Mexico, the US and internationally.

Soon scholars were speculating about the popularity of this Mexican icon, not least her association with growing levels of narco-violence and both the risks this posed to vulnerable social groups, but also the growing presence of the cartels themselves within society.

It is no coincidence that La Santa Muerte’s contemporary popularity took off, therefore, in an atmosphere of increasing violence.

As the author notes, whoever can control images gains a form of power, which explains why the church was soon fretting about the cult.

Catholic religious authorities, including Mexican bishops and the Vatican, began to urge their congregations to reject La Santa Muerte.

Such power and the fear that it invokes flows through imagery, and Lamrani’s focus is the complex relations between death, the dead, the saints, and between popular religiosity and images. The theoretical lens with which she explores these focuses on the notion of intimacy.

She writes: “Although images have ended up constituting the crowded visual background of our social lives, it is the kinds of intimacies they elicit that make them powerful.”

Lamrani’s central concept is the intimacy of devotees with death imagery, which she argues directs the study of La Santa Muerte beyond the devotional, religious realm to incorporate within it the immediate, secular and material concerns of worshippers.

There is little doubt that Mexicans have a particular cultural intimacy with death—consider how Day of the Dead commemorations have gained global attention—but especially in the context of violence.

Lamrani writes: “La Santa Muerte, invokes sacred and political obligations in a country deeply infused with death. It also offers a fresh perspective on Mexico’s contemporary history in the light of the senseless brutality that has sown dead bodies all across the Mexican Republic…

“Violence has infiltrated every aspect of daily life to permeate the realms of politics, society, and religious beliefs. It has now become distressingly familiar, an intimate presence in people’s lives.”

The controversy surrounding this saint, she argues, reflects “a muted terror, a quiet unease and sense of desperation that has become so entrenched in daily life that it provokes a particular kind of resignation in the face of death.”

Moved by the Dead: Haunting and Devotion in São Paulo, Brazil, Michael Amoruso, 2025, University of North Carolina Press

Suffering sustains the relationship between the living and the dead, suggests Michael Amoruso at the beginning of this book.

And it is the souls of the dead who endured particular suffering in life that often gain most spiritual power in their ability to help the living.

A striking example of that are the tombs of 13 unidentified victims of a notorious fire in São Paulo in 1974, when flames consumed the Joelma high-rise office tower leading to traumatic scenes that scarred the Brazilian psyche.

About 200 lives were lost that fateful day to the conflagration, which could be blamed on a complex set of factors from weak building codes to an under-resourced fire department in the rapidly growing metropolis.

But it was the victims who could not be identified, laid to rest together after two public funerals, who have become the focus of pilgrimages and prayers on the “day of the souls”, Mondays, when visitors often make votive offerings for graces received.

The cult of the souls, the author argues, furnishes “a ritual grammar for transforming trauma into devotion”. It is an example of what the religious studies scholar Robert Orsi observed was one of the roles of religion, which he said “is less about the making of meaning than about the creation of scar tissue”.

Intrigued by such devotions to the dead, Amoruso notes that such practices—devotion to souls—are widespread in Brazil and treat the dead as saints, using candles, prayers and novenas to petition their help.

The 13 victims of Joelma aside, a first defining aspect of devotion to souls is that they are invariably indefinite in number and that what defines them is their category: afflicted, forgotten, hanged etc.

A second characteristic is their suffering, either in life, at the moment of death, or in the next world, which the author suggests helps us make sense of this devotional practice’s “capacity for understanding social violence”.

But it is the anonymity and ambiguity of these victims that appear to be particularly important, he argues, by contrast with devotions to named saints.

He writes: “In contrast to the cult of the saints, the devotion to souls is a way of remembering forgetting. It thrives in the epistemological wound opened by neglect. And far from resolving this neglect, the devotion dwells in it, directing attention to agents of erasure and opening up spaces of possibility.”

It is the mutual suffering of the living and the nameless dead they pray to that binds both protagonists in this drama of urban religion.

“Devotees pray to ease the affliction of the suffering souls, who have the power to help the living in kind. Mutual suffering sustains a relationship of mutual aid between the living and the dead.”

In a broader sense through this altruistic reciprocity, Amoruso concludes, the practice connects the personal affliction of the devotees with the long memory of social violence in São Paulo.

Ultimately, it gains a political character by motivating devotees and activists to advocate for official recognition of historical injustices such as slavery. The dead continue to live through their suffering.

*Please help the Latin American Review of Books: subscribe for just one month ($5) and support our mission to offer readers more.