Unity written in blood and ink

Cecilia Vicuña’s Saborami was an iconic artistic statement of resistance to the 1973 Chilean coup that has now been reproduced. Georgina Jiménez interviewed her

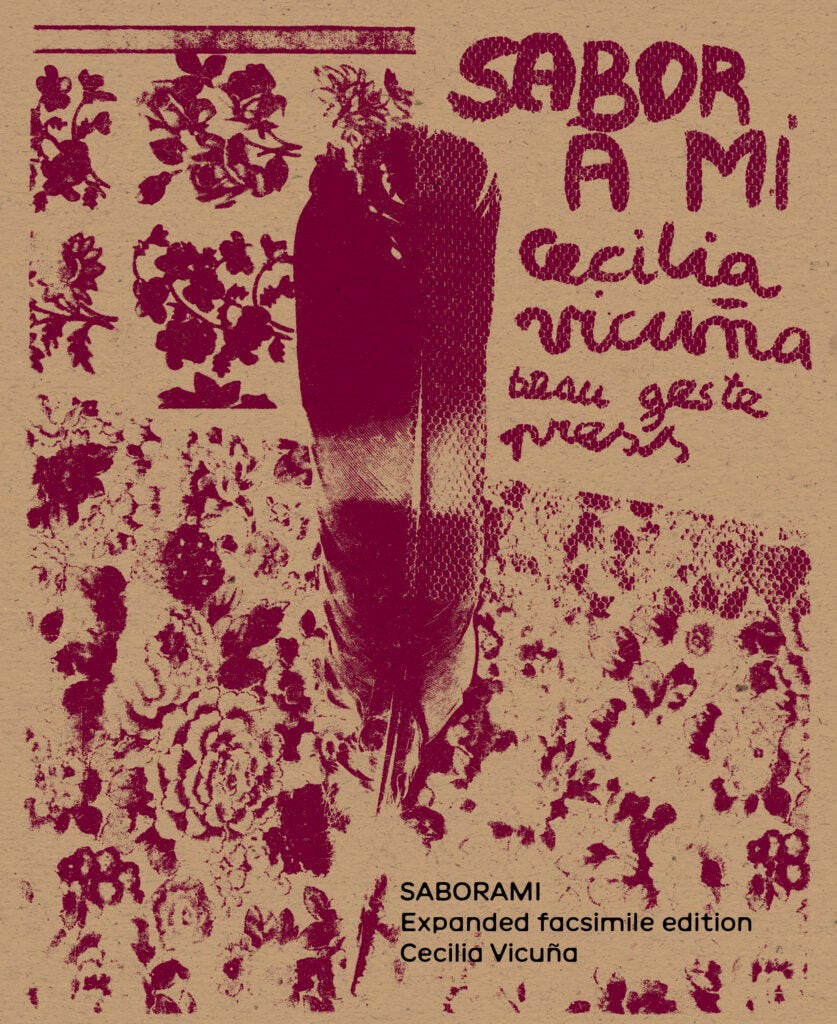

Saborami: Expanded facsimile edition, Cecilia Vicuña, 2024, Book Works

What do you get when you mix a continent in turmoil and a community of bright-eyed young exiles on the other side of the world? Electrifying works of art, profound voices, heartfelt testimonies—and incredible parties.

And after 50 years, it seems the defeat of Salvador Allende’s Socialist Chilean government in 1973 has still not extinguished the flame and that, through solidarity and love, Saborami begs reading anew.

The original edition of this iconic book by Cecilia Vicuña—an internationally renowned visual artist and poet—was produced in the UK in October 1973 in the immediate aftermath of the fascist coup under Augusto Pinochet.

One of the first artistic responses to the violence of the junta, combining poetry, journal entries, documentation and paintings, it was published on a shoestring in Devon in an edition of 250 hand-made copies printed by the artist-led Beau Geste Press.

We caught up with Vicuña, who has worked as a political artist out of the limelight until recently, at the launch of a facsimile reproduction of this historical document at the Tate Britain gallery in London.

Saborami—sweetly named after the favourite bolero of the author’s mother’s—was a response to a political catastrophe, and the shattered hopes of a whole generation of socialists in Latin America. As a literary source, it is a work that restates a commitment to art, imagination, political life and togetherness. In many ways, it was years ahead of its time.

This facsimile reproduction comprises archived documents ranging from texts and accounts written or given by the author in the 1970s, and for the first time includes coloured illustrations of different objects from the journal of the Chilean resistance.

In artistic terms, the images it contains can be considered as a chronicle of Vicuña’s creative practice up to the year of 1973. Her works explore Indigenous spirituality, memory, and language. The decolonisation of industries that have imposed an alien way of life on the Indigenous community is another one of her themes.

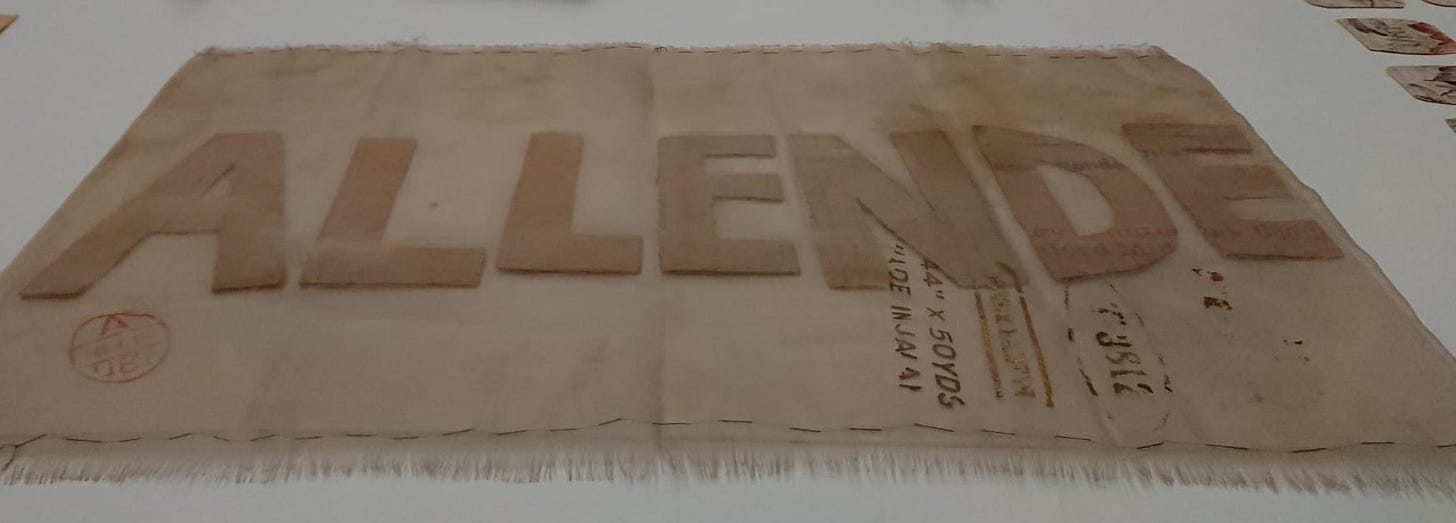

Vicuña was the founder in the 1960s of La Tribu No, a group of poets and artists, edited the No manifiesto de la Tribu No, and has produced films and installations. From the late 1960s to the early 1970s, she was involved in the Popular Unity movement in Chile that would bring Allende to power.

Saborami is a reverse chronology, beginning at the moment of crisis with the “Precarios” (sculptures from a collection of objects that Vicuña found in the street) and moves backwards through notebooks, installations and paintings, ending in poems written by Vicuña before leaving Chile. In 1972, she won a scholarship to attend the Slade School of Fine Art in London, but the events in Santiago meant that she would remain in England. The works after the “Precarios” inform us about how her life was affected by the coup.

When speaking about her involvement in Popular Unity, Vicuña finds those two words somehow painful, and asks what has happened to humanity, as the dehumanisation of modern life is brutal. She says: “Fifty years on from the coup and perhaps there is a drought in our souls as much as there is in the Earth now. As I see it, Popular Unity was the last expression of the sprouting forest, of the mestizo, Indigenous, people of Chile.”

Intellectuals, peasants, and students all formed part of this progressive sociopolitical movement that had its origins at the start of the 20th century, in which three generations of her own family were involved. Vicuña remembers her grandfather being invited at some point to join miners in this fight for justice. When farmers and workers attended rallies with their tools, a young Cecilia attended carrying a brush, like a magic wand, puzzling everybody. In a vision of communal property, she thought, “As industries are nationalised, I am nationalised.”

The feeling of togetherness infected everyone with a desire to be united in a journey towards justice. “This is what we all need right now,” she says, even when the expression Popular Unity has been distorted by the Chilean press to this day.

Vicuña remembers her arrival in London, and feeling an air of sadness and depression, but soon realising there was a “gorgeous energy of ‘Let’s do this’”. She says the spirit that she had been infected with in Popular Unity was replicated among the artists in London and she could be totally free. There was nothing cold about the joyful English, Scottish, Irish, and Welsh artists she encountered: “In the photographs you can see how this incredible life was welcoming. There was solidarity, a way of feeling for one another, a spirit of poetry at the time.”

She was given a studio in Stepney Green by the Arts Council where her friends would hold outrageous parties that included exiled Africans, Uruguayans, Brazilians, and Scots, Irish and Welsh felt part of the exile community too. “It was beautiful,” she says, and she created a committee and became a union speaker in pubs.

Being an artist was part of that revolutionary, universal movement, she notes, and solidarity was instantaneous and spontaneous. Everybody looked up to the Chilean revolution—it was participatory and everyone contributed something.

Vicuña’s first show in England was held at the ICA after she had written to them—the director replied that her art could be displayed in the hallway leading to the toilets, so she accepted the space.

The initial idea behind Saborami was to make a sober and elegant artistic statement of photographs in black and white of her “Precarios”, but then the coup took place and everything changed.

Vicuña reflects on how the 1960s and 1970s was an exhilarating period because there were so many avant garde movements in various countries. Few Latin Americans were living in London at the time, but the Mexican artist Felipe Ehrenberg, who had been a contributor to the bilingual beat magazine El Corno Emplumado which had shut immediately after publishing a condemnation of the 1968 Tlatelolco student massacre in Mexico City, was living in England and formed part of the Beau Geste commune. At some point, Cecilia was published by El Corno, and she joined Ehrenberg in Devon. Beau Geste was one of the most influential avant garde independent presses of the post-war period, regarded by art historians as one of the most significant transnational collaborative projects of the 1970s.

The Tlatelolco massacre in October 1968, when Mexico’s military murdered at least 400 students following a series of large demonstrations, was a key moment in the country’s Dirty War, during which the US-backed PRI government violently repressed its opponents

Vicuña says: “I believe historically that massacre initiated all the massacres that went on in Latin America afterwards—including Chile.”

The original Saborami was hard to produce, the offset printing machines were noisy, and the artist had to pay for everything: “At the time I had £40 and all that money went into the book. Production was difficult as no one had any money and we used every possible resource available, we even kept the paper used in the sacks of animal feed for printing, I dyed it blue in made-up batik. That’s why all the 250 copies were different, we used the poorest materials.

“Everyone in the 1970s was penniless, but we produced beauty without money, just with ingenuity. Ehrenberg’s English was worse than mine but the book needed to be produced in English. Joyfulness, humour even at that moment of defeat, shows that we didn’t give up.”

She adds: “In the beginning I was trying to prevent the coup, but by now the objects were intending to support the armed struggle against the reactionary government—they were trying to kill three birds with one stone: politically, magically and aesthetically.”

In 2018, work on reproducing the book started under Dr Luke Roberts, senior lecturer in modern poetry at King’s College London and author of Home Radio, and Dr Amy Tobin, associate professor in the history of art at the University of Cambridge and author of Women Artists Together: Art in the Age of Women’s Liberation.

Vicuña fears that the new technology of artificial intelligence risks a very powerful form of disinformation threatening the rise of fascistic military governments all over the planet, including Chile. She notes that in her country the far right is resurgent.

“I call for citizens to express ‘Indianness’ [a term coined by her] by adopting a view of the world that has been supressed because it is a collective view about engaging deeply with all beings, not just human beings. This is the way I grew up because my mother is an Indian [Indigenous], I have heard her speak with the trees, with the animals.”

What we need more than ever, she says, is togetherness, and asks: can we manage to create a feeling that can speak to those who cannot feel and create bridges?

“This is the challenge: to remain human, because indifference is like a disease, apathy is the opposite of humanness. Political discourse in the last three years has shifted, and if this human ability to feel the pain of the other disappears it is not worth being human anymore.”

It is a hope that could emerge just by opening the pages of Saborami.