Pilgrims and progress

An ancient Oaxacan icon sheds light on the modern meaning of pilgrimage. Books in brief: Devotion in Motion: Pilgrimage in Modern Mexico, Edward Wright-Ríos, by Gavin O'Toole

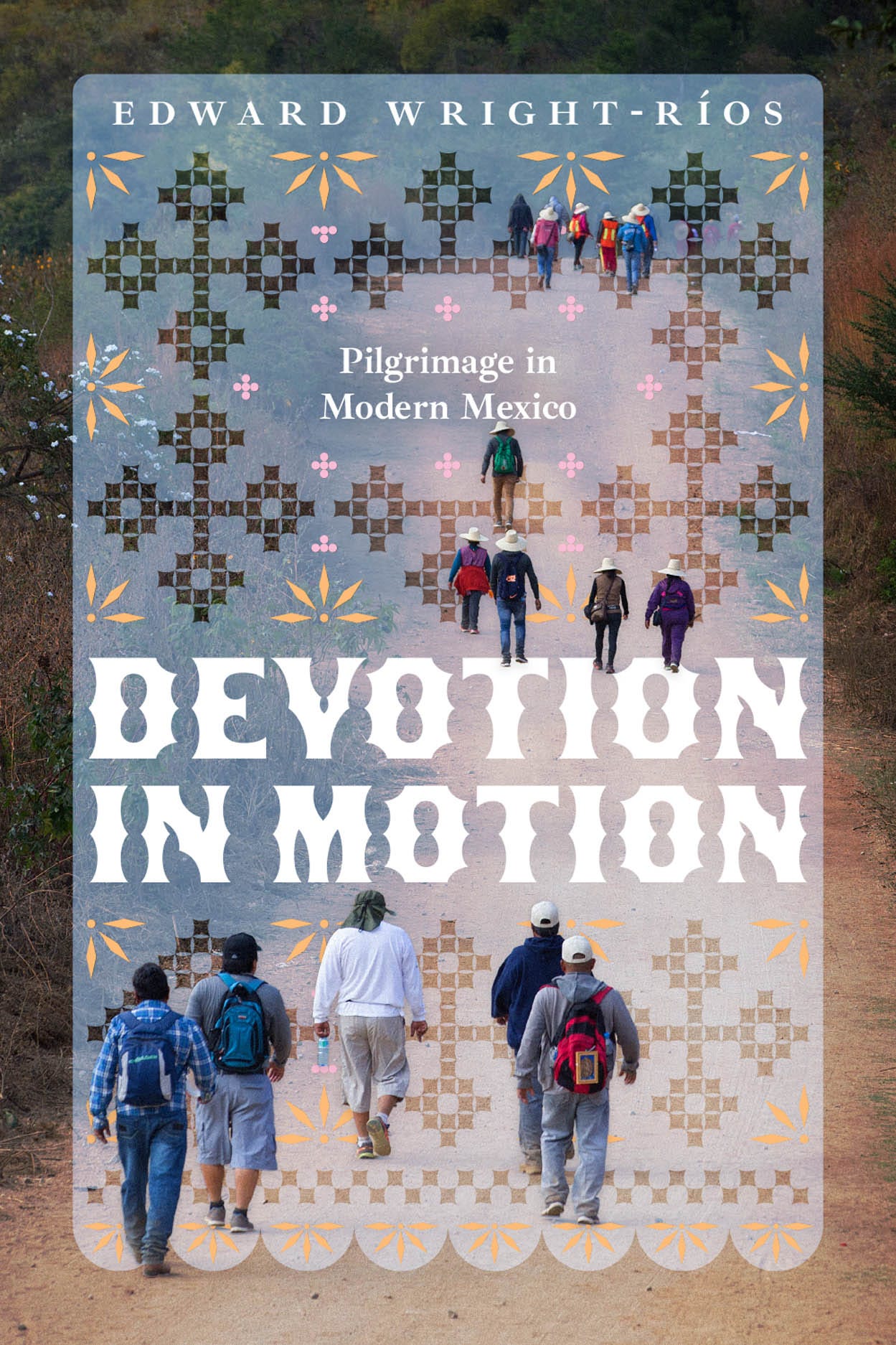

Devotion in Motion: Pilgrimage in Modern Mexico, Edward Wright-Ríos, 2025, University of Chicago Press

The Mexican pilgrimage is often depicted as a quaint cultural artefact enthusing a zealously religious congregation that is overwhelmingly rural, mostly Indigenous and peasant in their traditions, and ultimately resistant to modernity.

In the case of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the official Catholic patroness of both the Mexican nation and, indeed, the Americas itself, it is also the expression of a more secular affiliation to a national identity that formed the backbone of the modern state.

Guadalupe is the most well-known and popular of all image devotions in Mexico with her shrine at the foot of Tepeyac drawing millions of pilgrims every year, and if you visit this it’s not hard to see why.

Her image, reflecting stories of her sixteenth-century apparition to an Indigenous peasant on a hillside outside Mexico City and its miraculous manifestation on his cloak, embodies the country’s mestizo popular nationalism.

Yet as Edward Wright-Ríos notes, the Mexican pilgrimage is far from being a reenactment of a premodern rite and “remains a dynamic facet of present-day cultures, a living practice woven into the lives of people who are very much part of the modern world”.

Devotion in Motion: Pilgrimage in Modern Mexico is an eloquent study of this phenomenon by a Mexican American writer himself steeped in Catholic tradition with a careful scholastic eye for the many nuances of this practice.

Wright-Ríos takes as his focus the Virgin of Juquila, a small one-foot-tall wooden statue from the late sixteenth century that resides in the santuario of Santa Catarina Juquila, a mainly Zapotec-speaking community in Oaxaca.

This icon draws perhaps 2.5 million visitors to the town every year and as the author points out, her devotion pervades everyday life through stickers, magnets, T-shirts, statuettes, caps, and pictures bearing her likeness, posters, photos, and altars in stores and homes, testimonials stencilled across windshields and dashboards, and the names of butchers, bakers, printers, mechanics and countless shops.

As part of his study into what drives those who travel to venerate the virgin, Wright-Ríos joins a pilgrimage, and the results of his research are enlightening.

The book is far from being “a wistful portrayal of a uniquely devout people and unalloyed faith” but is an examination of people caught up in a modern hectic existence and rapid technological change who nonetheless embrace the pilgrim’s journey of self-discovery.

On the way, they do not seek to recreate “a purist, preservationist crusade” but reconfigure customs with new meaning, new fashions for expression, organisational techniques and technologies.

As Wright-Ríos writes about his study: “It reveals that pilgrimage, in fact, isn’t old at all.”

Above all, it is dynamic, because each generation of travellers adapts and reinterprets what they are doing amid new social contexts and cultural pressures in order to give their journeys intimate personal meaning in a contemporary context.

A clear sign of this dynamism is the role social media now plays among pilgrims, with Facebook and YouTube rapidly evolving into key forms of expression for devotees and important tools for those who lead pilgrimage groups.

Moreover, the pilgrimage and shrine have become essential to the local economy—state authorities in Oaxaca estimate that 731 local jobs are directly dependent on them and the annual flow of devotees sustains an additional 1,882 workers indirectly.

Wright-Ríos has cast a careful eye on the many meanings of pilgrimage, the personal stories of those involved, and the role it plays in contemporary Mexico, and what he has learned is that this is far from being an artefact.

He writes: “Pilgrimage is many things at once and constantly in flux. In fact, the value in studying it resides not in understanding ‘tradition’, but rather in appreciating the complexities of change.”

*Please help the Latin American Review of Books: you can subscribe on Substack for just one month ($5) or, if you like what we do, you can make a donation through Stripe or PayPal (send your PayPal contributions to editor@latamrob.com