The territorial turn

The US attack on Venezuela confirms that imperialism is all about space. Review: The Invention of Order: On the Coloniality of Space, Don Thomas Deere, by Gavin O'Toole

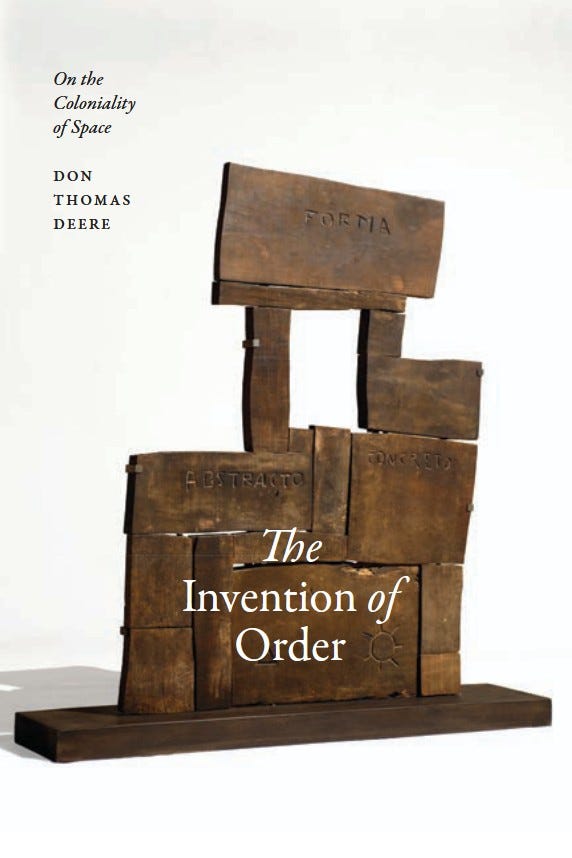

The Invention of Order: On the Coloniality of Space, Don Thomas Deere, 2025, Duke University Press

The attack on Venezuela confirms that US aggression towards Latin America has entered a dangerous new phase in which territory is now at direct risk of colonial expansionism.

While the attack was timed to distract attention from mounting accusations that the degenerate Trump was feeding on the carnal feast served up by paedophile Jeffrey Epstein, it is an auspicious time to discuss the territorial dimensions of his reign.

Indeed, if there is any mechanism by which we might best seek to characterise Washington’s new approach to foreign policy, it is spatial.

Like a capricious Caesar, Trump is becoming obsessive about territory, undoubtedly a legacy of his chequered career as a grubby real estate hawker.

His point of departure appears to be a crude interpretation of the US border as a line separating civilisation and barbarism that must be reinforced but, moreover, revered.

The new “others” in the Maga era are the dusky narco-terrorists who lie beyond—and to secure the narcissist’s personal, imperial legacy, that border must be expanded.

The abundant natural resources of Venezuela, already prey to the excessive greed of US oil majors, will undoubtedly come under American control as a result of Trump’s first major territorial adventure in Latin America.

But it is a signal to Europe as much as anything: he has also made dark hints about using military force to take control of Greenland.

He has repeatedly insulted his neighbours in Canada by coveting this vast country as a US state. He has threatened to send troops into Mexico (presumably coveting its territory as well, as so many racist former US presidents have) and to seize the Panama Canal (again).

His approach to the Gaza conflict has been that of an avaricious landgrabber, aligning with Israeli greed to treat the tormented enclave as a prime beachside real estate opportunity with no regard whatsoever for the humanity of its occupants.

And his attitude towards talks to end the bloody Ukraine war is so transparently aimed at maximising US exploitation of the country’s resources, ideally in league with his Kremlin allies, that it feels mediaeval.

As Trump is demonstrating beyond doubt, “space” matters in the study of international relations, and hence by definition in the study of colonialism, and that is especially so under the “realist” understanding of power by which Washington now operates.

All this helps to explain why space is becoming an increasingly important concept in decolonial theory—and to resistance within societies.

Social movements, for example, challenge the state by seeking to exert physical control over symbolically important areas, from the yellow vests in France to the Occupy Wall Street protests in the US itself.

In many of these protests, public space is reimagined as a site of resistance: in Spain, the Indignados established “police-free zones”, occupied hospitals to save them from privatisation, seized unused land and homes, and created urban community gardens.

Spatial relations repeatedly come to the fore in the study of Latin American human geography in which, as the Marxist David Harvey has argued, struggles for control of land and territory have been defining traits in the evolution of capitalism.

Space has also shaped the discussion of racial, ethnic and gender identities in the work of authors such as Aníbal Quijano, Enrique Dussel and María Lugones, with Indigenous and Afro-Latino communities, for example, segregated and subject to the imposition of colonial identities.

It is for this reason that the problematic of space has been a central theme not only in intellectual production of all kinds in Latin America—note for example, the notions of centre and periphery in the work of Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch—but also of more contemporary decolonial thought and critiques of coloniality.

Space has been an important theme in philosophy, not least in the work of Foucault that traced the evolution of mechanisms by which power is exercised in modern societies.

Foucault was a key figure in the so-called “spatial turn” in the humanities and social sciences by imagining spaces where discourses on space come into contact with physical space in its architectural, urban and institutionalised forms.

Mental hospitals and prisons, for example, were social spaces where discourse and thought are regulated by prevailing relations of power, space and knowledge.

But as the Colombian philosopher Santiago Castro-Gómez points out in his Foreword to Don Thomas Deere’s The Invention of Order: On the Coloniality of Space, Foucault’s technologies of power oriented towards the discipline of bodies and the governance of populations were ascribed to 18th-century Europe.

What Deere does, with a nod to the work of thinkers like Quijano and Dussel, is argue that these technologies were products of colonial interactions in the American colonies, used to control Indigenous and Black populations, and hence that they originated outside Europe.

These spatial practices reinforced discourses that presented Europeans as civilised and the colonised peoples as barbarians, justifying narratives of superiority while delegitimising the knowledge produced by local communities.

On one side, Europeans saw their own space as organised and accounted for; on the other side, empty space, free for exploration, discovery, and appropriation.

Indeed, colonisation of the Americas represents the very moment in which modern “order” was invented, a spatial transformation at the very heart of which resided a European notion of “empty space”.

As Deere argues, the other side of the line is defined by not only ontological negation and emptiness—but also the production of a whole regime of order, connected to disciplinary and racializing practices that is also at the heart of modern systems of knowledge.

Deere writes: “A notion invented by European practices and sensibilities in justifying colonial conquest, empty space is practiced by depriving existing Indigenous, African, and mestizo populations of their spatial distributions and rights to land.”

It is a powerful notion that immediately calls to mind Trump’s twisted worldview, by which within the US border can be found order, while outside lies the chaos of lands free for exploration, discovery, and appropriation.

It may also be evidence that spatial order continues to be defined in the Americas with Europe as its intellectual audience—Trump’s Venezuelan escapade is also a signal to Denmark that he intends to seize Greenland.

Deere argues for a spatial reading of modernity, whereby modern thought is created and shaped through a global emptying and ordering of space.

Modernity, he suggests, “takes place in a global battlefield of space that seeks to neutralize and eliminate other modes of spatialization while imposing and producing a single unitopic model of space.”

To understand the practice and organisation of modernity, therefore, we need to analyse the production and ordering of space.

His ambitious work is built on a critique of traditional accounts of modernity—from the philosophies of Hegel, Weber and Habermas, for example—whom he argues failed “to think the map of modernity”.

For Hegel, Deere argues, “the Mediterranean was the model of the concentration of history: the space where history reached its highest point of dialectical perfection”.

He writes: “Their cartography is Eurocentric while also pretending that space is neutral and empty, just a container. Modernity is, in this sense, inscribed as a temporal concept by its very name: To be modern is to come after, to have followed a line of exclusively (or ultimately) European development and progress. By the eighteenth century, the spatial dimensions of modernity will be embedded in temporal terms of progress: maturity versus immaturity or modern versus primitive.”

This perspective draws Deere naturally towards a tradition that had developed among Latin American thinkers who began developing an understanding of the relationship between space, colonisation, and modernity in the middle of the last century.

In The Invention of Order, the author develops a historico-genealogical account of the ordering of space in the Americas from the 16th to 19th centuries, the expansive span of history from colonisation to nation-building.

He explores the implantation of urban grids in 16th-century colonial cities, which immediately take on disciplinary and racializing roles while enabling the extraction of resources.

He analyses how the Americas were conceptualised as an empty space free for European projects and shows how this is accompanied by the codification of certain spaces as free for the movement and settlement of certain racial subjects.

Deere proceeds to draw on contemporary reflections about spaces of resistance in the past and future of modernity in Latin American and Caribbean thought,

He develops in particular a spatial reading of Dussel’s history of modernity and how the material invention, production and silencing of the non-European is at the root of European claims to universality.

Dussel’s “transmodernity” suggests that embracing a truly global conception of modernity requires overcoming the violent excesses of the Eurocentric modernity with a “pluriversal” notion of reason.

Finally, Deere considers practices of resistance to the modern global project of order and how this can be advanced in the aesthetic imaginary through alternative modernities, with a focus on Édouard Glissant’s novel Caribbean geopoetics.

Glissant’s underlying ambition is for an acceptance of difference without hierarchy in place of the certainty of Europeanised “Otherness” based on an acceptance of “opacity”—a notion that contains the radical potential for social movements to challenge systems of domination.

Deere’s study of resistance compels him to conclude with a sense of hope that the colonial order is always subverted—hard as it may be to swallow as the US bombards Caracas.

“Domination is never complete,” he writes. “From Lugones to Glissant, from Dussel to the Zapatistas, from the sea to the shoal, from the mangrove to the mountain, from the jungle to the city alleyway—there remain ways to redraw the map, to move beyond its imposed lines.”

*Please help the Latin American Review of Books: you can subscribe on Substack for just one month ($5) or, if you like what we do, you can make a donation through Stripe or PayPal (send your PayPal contributions to editor@latamrob.com

"Domination is never complete" gives me hope. To me it means that a part of the history or culture will remain in the "order". Thanks for introducing me to Deere

Excellent analysis 👏🏻