The threat doctrine

The legacy of Cuban internationalism in Africa still defies US hegemony. Review: Cuba and the Independence War in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, Víctor Dreke Cruz, by Gavin O'Toole

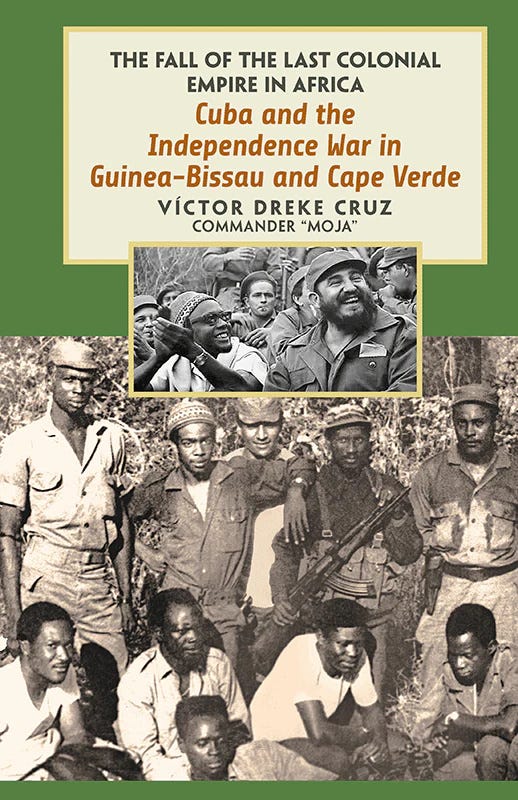

Cuba and the Independence War in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde: The Fall of the Last Colonial Empire in Africa, Víctor Dreke Cruz, 2025, Pathfinder Press

There is an intimate, if inverse, relationship in international relations between multilateralism and the degree to which states threaten—or feel threatened by—each other.

That is because when multilateral relationships are intentionally weakened, what prevails is raw power which, inevitably, is exerted by strong states against weak ones with prejudice.

In short, narratives of “threat” are largely a byproduct of unilateralism and directly reflect the theoretical international relations framework of “realism” that views politics as an anarchic competition for power, security—and survival.

Donald Trump’s executive order to slap tariffs on countries that sell oil to Cuba, the latest nefarious step in Washington’s lengthy campaign of terror against Havana, alleges that its government poses an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to US national security.

In turn, this latest affront to Cuba’s independence has undoubtedly raised the stakes for the island considerably and hence increased the level of threat felt by its long-suffering people, a word that appears to be on everybody’s lips.

Small wonder, then, that Cuba’s President Miguel Diaz-Canel in denouncing Trump’s effort to “suffocate” the sanctions-hit country’s economy was at great pains to emphasise that Havana poses no threat whatsoever to the US or indeed anyone else.

It is difficult to emphasise strongly enough the substance of Diaz-Canel’s denunciation because few countries in the world have demonstrated their pacific intent, humanitarian commitment and internationalist credentials more than Cuba.

This is a country that exports doctors, not bombs, medicines not missiles, an army in white coats not trigger-happy gunslingers in khaki—and that has, as a result, saved hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of lives.

In October 2014, for example, some 250 volunteer Cuban medical internationalists arrived in Sierra Leone to battle Ebola, and within months had helped eradicate the deadly epidemic in that country, Guinea-Conakry, and Liberia—while capitalist Western nations fretted about security.

Another tragedy of Trump’s threats, therefore, will be the curtailment of Cuban healthcare aid in some of the poorest countries of the world under direct threat of US retaliation for accepting medical help from Havana.

We live in a world that demands greater clarity than ever before to cut through the fog created by imperialism and, as the African Union reminded us this week, that also demands vociferous statements of solidarity.

In a resolution warmly welcomed by Havana, the AU condemned the blockade against Cuba—for the seventeenth consecutive time—as well as its designation by Washington as a terrorist country in an effort to build a legal pretext for Venezuela-style intervention.

When it comes to international solidarity—and the defence of multilateralism—words matter, especially when they are grounded in history, and no region of the world understands this better than Africa.

A good reason for that is Cuba’s astonishing record of solidarity with African peoples in their struggles for freedom from colonialism—an aspect of its revolutionary history, but also postwar history taught in schools, which has been intentionally suppressed in a hostile West.

As Mary-Alice Waters implies in her introduction to Cuba and the Independence War in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, this is because the postwar anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist tide reached its political zenith with the Cuban Revolution right on Washington’s doorstep.

It was arguably the final nail in the coffin of racialised segregation in the US against a large component of the working class, which opened the door to the integration of the labour movement and transformed American race and class relations.

It is therefore no small irony that what we are witnessing today, alongside Trump’s direct assault on socialist Cuba, is his domestic effort to reverse the gains in racial equality that can be traced by a single thread back to the 1950s and 60s.

Cuba and the Independence War in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde provides the essential historical context for this analysis.

It is the remarkable account of Víctor Dreke Cruz—a leading, if somewhat overlooked hero of Cuba’s revolution and the subsequent importance it gave to liberation in Africa.

From Algeria to the Congo, Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Angola and beyond, hundreds of thousands of Cuban men and women gave concrete form to solidarity by participating in twenty-four missions in Africa over three decades.

Perhaps the best-known example of this international solidarity was the Cuban contribution to defending the newly independent Angola from apartheid South Africa between 1975 and 1991.

Dreke served twice in senior positions within Africa, in 1965 as second in command to Che Guevara of Cuban internationalist combatants in the Congo—where he was given the nom de guerre Moja (“One” in Swahili); and in 1967–68 as head of Cuba’s mission in both Guinea-Bissau, then fighting for independence from Portugal, and neighbouring Guinea-Conakry (Guinea).

Dreke headed the Cuban military instructors fighting alongside the guerrillas of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC); directed the Cuban volunteers training militias in Guinea to defend against imperialist threats; and from 1986–89 again served in Guinea-Bissau as an adviser to the armed forces.

These missions and the eventual liberation of these countries not only changed Africa, but also Europe—not least in 1974 when the fascist regime in Portugal was overthrown by a military coup that had been accelerated by demoralisation in the armed forces due to the defeats it was suffering in Guinea.

They were also a direct challenge to the expansive Cold War imperialism of Washington which, although it denied it, was arming and funding the Portuguese colonial wars.

Most importantly, these missions reflected a concrete consensus among internationalists—many of them brilliant revolutionary thinkers, such as the titanic Amílcar Cabral—forged at the 1966 Tricontinental Conference hosted by Cuba about the need to confront imperialism.

It is not hard to see why Fidel Castro and Che saw a kindred spirit in Cabral, who had stated at the 1965 Dar es Salaam conference of liberation movements in the Portuguese colonies that “our armed struggle is only one aspect of the general struggle of the oppressed peoples against imperialism, of man’s struggle for dignity, freedom, and progress. In the vast front of struggle in Africa today, we should consider ourselves as soldiers, often anonymous, but soldiers of humanity.”

In turn, Cabral welcomed the internationalist aid received from Cuba and, as shown by Dreke’s account of his leadership of the PAIGC, demonstrated great confidence in the revolutionary capacities of the exploited and oppressed.

Guinea-Bissau won its independence in 1974—and the following year Cape Verde, Mozambique, Angola, and São Tomé and Príncipe all became independent from Portugal as well.

Dreke’s Cuba and the Independence War in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde represents a firsthand account of the fall of this last colonial empire in Africa from interviews conducted by Waters with this Cuban revolutionary hero over nearly two decades.

Dreke provides a fascinating account both of Cuba’s involvement in the struggle and strategic lessons from the fighting, but also of Cabral’s inspirational leadership that ultimately led to the victory against imperialism on the battlefield.

One of those lessons was the strong moral framework that Cabral inculcated in his cadres—they were above all a political, not a military, movement who understood why they were fighting and what their political goals were.

As a result, says Dreke, combatants became conscious, dedicated fighters instilled with moral values who eschewed the terror and abuses committed by their enemies. Portuguese prisoners of war were treated with dignity, and handed over to the Red Cross.

Cuba also provided doctors, a critically important resource for the PAIGC and wider community in an impoverished country that had none, and thereby sowed the seeds of medical education by giving classes and training Guinean women as auxiliary nurses.

The lessons of the rebel victory resounded throughout developing countries struggling to build a better life for their peoples, and Cabral came to symbolise for millions around the world the best qualities of an anti-imperialist leader.

As Dreke says: “Guinea-Bissau showed how a small African country—with a population of half a million at the time, with very little economic development, and a liberation army with few weapons and resources—could defeat an imperial power and a much greater military force.”

He adds that this victory also strengthened the “consciousness and confidence” of the Cuban people, a point alluded to by Miguel Diaz-Canel in rejecting the US narrative of a “failed state” collapsing under overwhelming imperialist pressure.

Revolutionary Cuba does indeed remain a threat to the US—but one comprising the potential of multilateralism and solidarity to resist a militaristic empire exerting a rawer, unilateral power.

This means Cuba’s future, as has been its past, will be decided by the appetite of other countries for international solidarity—one hopeful signal of which has just been sent by the African peoples it has done so much to help.

*Please help the Latin American Review of Books: you can subscribe on Substack or make a donation through Stripe