Women at arms

Cuba’s revolution was not won just by bearded white men. Review: Clandestinas: Women in the Cuban Revolutionary Underground, 1955–1959, Carollee Bengelsdorf, by Gavin O'Toole

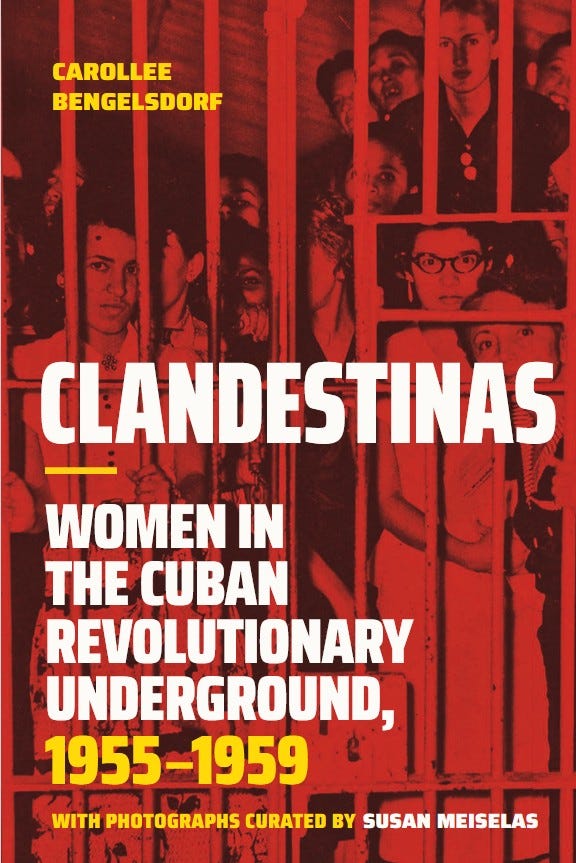

Clandestinas: Women in the Cuban Revolutionary Underground, 1955–1959, Carollee Bengelsdorf, with photographs curated by Susan Meiselas, 2025, Duke University Press

The most intriguing episode in Latin American guerrilla warfare since the Cuban Revolution was the insurgency of Sendero Luminoso in Peru.

The devastating effectiveness of this rebel group during the 1980s captured global attention as its cadres extended a “people’s war” from the highlands to cities where the elites waited—literally quaking with fear.

Sendero Luminoso established a reputation as the most brutal and ideologically strident insurrectionary group of the 1980s, pushing the Peruvian state to the brink of collapse in a civil war that would claim 70,000 lives.

The rebels embraced the magic of fanatical terror to inspire fear in their enemy, inclined to hang dead dogs from lampposts in central Lima to denounce the betrayal of China by Deng Xiaoping, a “son of a bitch”.

Given Sendero’s use of extreme violence, what was perhaps most curious about this episode beyond the group’s avowedly Maoist ideology and strongly indigenous cadres, however, was the role of women.

The Senderistas were distinct for including a high proportion of women not only as combatants (50 per cent) but also as commanders (40 per cent). In the annals of revolutionary warfare, this has never been matched.

The organisation’s number two, Augusta La Torre, known as Comrade Norah, was a key figure not only in establishing such high levels of female participation but, more importantly, in providing an explicit theoretical justification for it.

This was most clearly outlined in a document Marxism, Mariategui and the Women’s Movement published by the organisation’s political wing in 1974 which, initially at least, confirmed women as fully equal class warriors in the people’s war.

Nonetheless, what subsequently unfolded within Sendero is what we have seen occur many times, as adulation towards male leaders fostered the development of a patriarchal cult of personality around Sendero’s founder, Abimael Guzmán.

By the mid-1980s, references to the liberation of women had mostly disappeared from Sendero publications at the same time as the rebels’ violence towards women displayed a disturbing pathology of sexism.

Similarly, from an historical point of view, while many scholars recognise the importance of women in Sendero, little work has since been published that considers gender dynamics within the Peruvian communist party.

One might even go so far as to suggest that, if the old adage “history is written by the victors” is undoubtedly true, then it is even truer to suggest that, when it comes to guerrilla struggle at least, “history is written by the men”.

This certainly seems to have been the case in Cuba, where the narrative of revolution and, extrapolated from it, of national identity achieved through armed liberation, has overwhelmingly been constructed upon, first, the notion of the guerrilla (the foco theory as it was called), and, second, the guerrilla commando’s composition primarily of bearded (usually white) men enduring valiantly in the sierra.

As Carollee Bengelsdorf shows in Clandestinas: Women in the Cuban Revolutionary Underground, 1955–1959, addressing this is in itself subversive, by challenging our entire understanding of revolutionary Cuba to date.

The author explores the critical, perhaps even central, role played by young women in overthrowing the Batista regime during an insurgency fought not primarily in the sierra but in Cuba’s cities—the llano.

At the same time, she brings to our attention how this reality has been, and remains, largely erased from the legends of male valour and martyrdom in a battle fought against seemingly impossible odds that have nurtured generations on the left, far beyond Cuba.

She writes: “In truth it is a misrepresentation of historical fact. In its telling of what is at best a partial story, it occludes far more complex, messy realities.”

Bengelsdorf researches and recreates the struggle of women in the revolutionary underground movement, mainly in Havana where the full force of Batista’s repressive apparatus was deployed.

She argues convincingly that national identity in Cuba since the wars of independence has been a male construct that excludes women as active subjects, and the way in which the story of the insurgency against Batista has been told simply embedded this fiction.

It’s a critically important observation that leads her into a longer exploration of the mechanisms by which male leadership has been consolidated in Cuba’s longer revolutionary history, and how women became national subjects mainly through obedience to their men.

Fidel Castro was at the heart of this enterprise, overseeing for example the February commemorations of the men who died in and just after the Granma landing, by which he asserted an unchallengeable right as revolutionary commander to determine the form and content of nationhood itself.

In order to understand more fully the revolutionary role of women, Bengelsdorf asserts, one must understand the critically important struggle in the llano prior to and during the guerrilla war—at the heart of which were women.

The author says that dismantling the sierra-heavy history in this way is complex in the case of Cuba because, first, the story of the llano has been heavily suppressed in favour of the “official truth” cherished by the state; but also because there are no competing narratives.

Underpinning the official story is the figure of the “guerrilla”, and it is the centrality of this icon in Cuba but also beyond that explains why it is the sole representation of the insurrection that took shape in late 1958 following the failure of a general strike in the cities earlier that year.

Inevitably, the male guerrillas who took power would come to control the narrative and few published accounts by those who fought in the llano exist to provide any alternative.

However, Bengelsdorf shows how, after Fulgencio Batista’s coup in 1952 and long before the beginning of the guerrilla war, women were playing an integral role in denying the dictator legitimacy through opposition movements

This “time in abeyance”, as the period between Batista’s coup and Castro’s release in December 1956 following his imprisonment after the Moncada attack has been called, is largely empty according to the official narrative.

Nonetheless, it is of course the period when from civil society springs the entire anti-Batista movement, arguably beginning with the Frente Cívico de Mujeres Martianas whose insurrectionary actions Bengelsdorf argues came to constitute a critical force in the urban underground.

The author writes that while the official narrative of the triumphant 26th of July Movement position the Frente as a civic organisation that provided “sustenance” to the insurrection, “In fact … what emerges is a portrait of a group of women whose key members understood themselves as revolutionaries, as protagonists in the struggle to rid Cuba of Batista, and who acted strategically and tactically as such.”

The group made it their single purpose to rid Cuba of Batista by constituting a hub for drawing young women into the resistance, promoting and coordinating joint actions on the ground by different opposition groups, and staging their own confrontational demonstrations.

As part of her research, Bengelsdorf interviewed 31 former “clandestinas” who, during the insurrection, were aged 13 to 25, many of whom were imprisoned and tortured, especially black women.

She examines Che Guevara’s Episodes of the Revolutionary War as the earliest and most widely circulated account of the making of the revolution, and the comandante’s conception of the roles of women—sadly, undertaking predictable chores as cooks, messengers etc.

Yet the roles they played in practice went far beyond such a patriarchal view and included involvement in sabotage and bombing. For example, Mariíta Trasancos at the age of 15 was already involved in Action and Sabotage—a cadre brutally targeted by Batista’s forces—and played a key part in actions such as the Night of One Hundred Bombs

The participation of these women undoubtedly changed Cuba, but it also changed them, and as Bengelsdorf observes, by the time of Batista’s defeat and the triumph of the revolution, many were different people who could never go back to their previous lives.

She writes: “For most, this transformation inevitably led to a more critical awareness of the limitations of the society that in effect they had turned their backs on. And it was virtually impossible for them to somehow reintegrate themselves into their formerly preordained positions in household patriarchy or to return to the private sphere.”

Nonetheless, the author notes with irony that, if the lives of these women had taken a radical turn, “one key reality had not changed: the path the revolution would follow in the years after 1959 was not to be determined by women”.

It’s a bitter pill to swallow, yet Bengelsdorf seeks to tease out the real-life consequences of the Cuban revolution’s official narrative as it has been told, not only on the island itself.

She suggests that the effect in the Third World of foco theory—a revolution made in the countryside and mountains by a small band of guerrillas and exaltation of the role of the sierra—“was nothing short of tragic … establishing for decades a profoundly misleading blueprint for revolutionary change”.

This poses particularly important questions for feminists, by drawing attention to the uncomfortably stark reality for the Left that “no modern revolution or really any revolution has ever portrayed women as anything but at best secondary actors: men have always been the protagonists, in both physical and ideological terms”.

While feminists have sought to rescue the names of individual women who played key roles in various revolutions, they were often then celebrated for duplicating male behaviour, while such research simultaneously made invisible the actions of the masses of women inevitably involved in any societal upheaval.

This is not the first history of the role played by women in Cuba’s revolution—Michelle Chase and Lorraine Bayard de Volo are among others who have made important contributions to this field.

Nonetheless, it’s an important time to be highlighting this issue—making Bengelsdorf’s book required reading—as the US regime musters its forces again in the Caribbean ostensibly against Venezuela, but with one eye clearly on its ideological nemesis in Cuba.

Indeed, the women of the llano may find themselves being called upon sooner than we think to defend the revolution their foremothers fought for.

*Please help the Latin American Review of Books: you can subscribe on Substack for just one month ($5) or, if you like what we do, you can make a donation through Stripe or PayPal (send your PayPal contributions to editor@latamrob.com

The book, and this post, make important points about the subversive activities of women in 1950’s Cuba against the Batista dictatorship. My own cousin, aged 16 at the time, was detained twice for disseminating antigovernment propaganda. It was a miracle she was released unharmed. She was irrationally headstrong and the model for one of the characters in my novel about the Communist Revolution of 1959.